Aylesbury Vale Area Design Supplementary Planning Document

4. Establishing the structure

4.1 Natural Resources

Figure 4.1: INDICATIVE SITE CONCEPT PLAN 1 - Identifying natural features and resources

Principle DES9: Work with the natural features and resources of the site

Natural resources are the assets or raw materials found in the land and water including soils, vegetation and animal life. They provide vital services such as pollination and water purification and also wider benefits for placemaking and health and well-being.

The existing landscape structure and physical characteristics including geology, landform, watercourses and drainage, field patterns, vegetation and trees should be considered by applicants from the outset when developing a proposal for their site.

Priority habitats and locally distinctive features, such as those listed below, should inform development layouts and be retained and incorporated into the landscape structure:

- Waterbodies;

- Woodland;

- Trees;

- Hedgerows;

- Traditional orchards;

- Meadows;

- Wetland;

- Fens;

- Heathland;

- Open mosaic habitats; and

- Arable field margins.

Reason

4.1.1 Existing natural resources and features are valuable and irreplaceable assets of every site and the wider environment, contributing to the overall character and sense of place. The value of existing trees, vegetation and hedgerows should be recognised by the applicant, as they provide landscape continuity, history and value as the basis for a scheme as well as giving proposed new development an immediately mature element. As such retention and enhancement should always be the preferred solution and in some cases will be required as set out in VALP policy NE1.

4.1.2 Trees, hedgerows and other forms of vegetation also provide biodiversity and wider ecosystem benefits, and therefore any removals should only be considered where retention isn't possible and they must be compensated with an appropriate replacement The Mitigation Hierarchy Guide should be used in the approach to existing natural resources of a site following the four steps to firstly avoid, then minimise, restore and lastly, offset. Application of the hierarchy should result in the incorporation of trees and vegetation into the design, with an overarching aim for net gain in biodiversity.

4.1.3 Trees, planting, hedgerows, open landscape and ditches not only provide ecological benefits, but can provide a helpful structure to new development whilst enhancing its setting and reducing impacts on the wider landscape. Ponds and watercourses are beneficial features for enhancing views and outlook, whilst specimen trees draw visual focus and provide landmarks in new development. Any new planting should have a clear design objective which takes a 'right tree, right place' approach whilst not adversely impacting on biodiversity.

4.1.4 Important existing uses and functions of a site should be incorporated into a development through new or retained buildings, or landscape features. This includes existing informal routes and desire lines which should be acknowledged and potentially formalised.

4.1.5 Site constraints and opportunities should be considered from the outset of a project, with every effort being made to avoid disruption to below ground archaeology. Where possible, overhead electricity lines should be relocated underground, and along with other utilities, should be aligned with streets for ease of access and to avoid restrictions on planting in areas of open space.

4.1.6 Best practice guidance includes 'Biodiversity Net Gain: Good Practice Principles for Development, A Practical Guide' and 'Trees, Planning and Development A Guide for Delivery.'

Levels and grading around an existing retained tree were poorly resolved leaving the tree on an 'island'

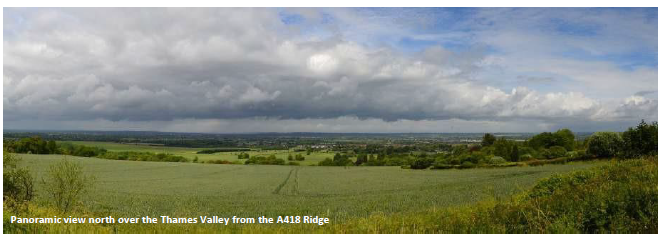

Principle DES10: Respond to topography and strategic views

All development, including residential, large scale transport infrastructure and communications corridors should use the existing topography of Aylesbury Vale as a framework for structuring the layout of a site.

Applicants should identify important views into and out of their site. This may include long distance views to landscape features or buildings, or shorter distance views to attractive or distinctive townscape. Development should be laid out so that these views are retained and where possible enhanced, to both improve legibility and the setting of development. New development should be structured to retain visual connectivity to adjacent features which will enhance legibility and identity.

Applicants should avoid siting buildings on the highest part of a site, using the natural shape of the land to help visually contain and soften the appearance of the development, avoiding breaking the skyline or ridgeline of hills. New development should not cause significant negative impacts particularly to and from the Chilterns AONB, or any other sensitive viewpoints.

Development should be grouped with existing buildings where possible to minimise visual intrusion, and any adverse effects regarding on-site and off-site views towards important features and landmarks should be limited.

Applicants should also consider how landform and topography will influence surface water collection and structure their development proposals to respond to this.

The spacing, height, scale, plot shape and size, elevations, roofline and pitch, overall colour palette, texture and boundary treatment of any development should be carefully considered.

Reason

4.1.6 Aylesbury Vale has a distinctive landscape of low undulating topography dissected with ridges of higher ground which provide attractive views across the open countryside. Views to and from The Chilterns AONB are particularly important for developments surrounding Aston Clinton, Aylesbury, Cheddington, Stoke Mandeville, Wendover, Weston Turville, all of which have public vantage points towards the AONB.

4.1.7 Careful consideration needs to be given to the topography of a site, and how the natural landform can determine views in and out. The visual connectivity to a site's surroundings can be enhanced through careful layout and massing design, with viewpoints and landmarks an essential consideration. Use of the surrounding landscape as an asset can help enhance the character of the development.

4.1.8 Natural landform should be analysed and considered to determine overall structure of development, views in and out of site, movement and recreational routes, building orientation and massing of development. Local changes in landform levels can either visually contain or increase visibility of development, determining the overall visual impact on surrounding neighbours. Existing landform of an area and its natural pattern of drainage should be investigated and reflected within a site's sustainable drainage (SuDS) system

Principle DES11: Establish a landscape and green infrastructure network

Existing green infrastructure and features on site should be identified and incorporated into scheme design. Green infrastructure adjacent to a site should also be identified and applicants should consider how new features on a site connect to the existing features both on and off site, to create a connected network of landscape and green infrastructure.

The structure and form of landscape and green infrastructure should be planned for at the start of a project and inform the layout of the development. Centrally located public open space and green infrastructure within a safe location that is overlooked, is preferred. Locating green infrastructure on the edges of a site should be avoided unless there is a need to create a buffer and it is appropriate to the context.

Applicants should create links between existing and proposed green infrastructure to further establish a high quality, multi-functional, accessible and connected network, with a clear role and purpose for each space to meet local needs.

Landscape planting should be native and use locally appropriate species, for example black poplar planting in boggy areas near ditches and floodplains. Edible landscapes should be encouraged. Heritage fruit and tree planting including orchards and species such as the Aylesbury prune or walnut, should be considered by applicants where appropriate.

Reason

4.1.9 There is a deficiency in green infrastructure in Aylesbury Vale, both in quantity and accessibility. In 2019, 69% of dwellings in the area did not meet Natural England's Accessible Natural Green Space standards. Two priority areas have been identified at North Aylesbury Vale and Aylesbury Environs, however all development over the minimum threshold must meet the minimum requirements set out in VALP policy I1 and appendix C.

4.1.10 Green infrastructure has a multitude of benefits, including, but not limited to providing recreation opportunities, visual amenity, creating habitats for wildlife, urban cooling, air quality regulation, adapting to and mitigating climate change, providing surface run off control, enhancing connectivity and through this encouraging walking and cycling, as well as having a positive impact on people's health and well-being.

4.1.11 Applicants should refer to the Buckinghamshire and Milton Keynes Natural Environment Partnership's "Vision and principles for the improvement of Green Infrastructure in Buckinghamshire and Milton Keynes".

4.1.12 A network of connected green spaces should be proposed through larger development sites, strategically located to maximise the benefits of existing green infrastructure and include open spaces which are centrally located within new development. This network should respond to, and soften the impact of development on, the surrounding area and existing heritage or landscape assets, and link to existing woodland, hedgerows and vegetation adjacent to site. The quality of all public open space should be driven through the aim for achieving Green Flag Status.

Homes overlooking a biodiverse wetland area

4.1.13 It is recognised that some species and habitats are particularly sensitive and some sites may not be suited to multi-functional uses including access. Care should be taken to reduce disturbance at these sites and to direct visitors to alternative green spaces to alleviate pressure.

4.1.14 Applicants should also use the Aylesbury Vale Green Infrastructure Strategy to inform and guide their decisions. The GI Strategy identifies ten local flagship projects which illustrate how to achieve multi- functional green infrastructure. The Buckinghamshire Green Infrastructure Delivery Plan includes proposals for Aylesbury Linear Park and Whaddon Chase, and new development around the area should deliver green infrastructure in line with both of these documents.

Figure 4.2: INDICATIVE SITE CONCEPT PLAN 2 - Establishing a green infrastructure network

A network of connected open spaces is proposed through the site.

These are strategically located to:

- Maximise the benefits of existing green infrastructure;

- Provide open spaces within the heart of the new development

- Respond to, and soften the impact of development on existing heritage assets;

- Link areas of woodland to the north and south of the site; and

- Protect, enhance, create and connect biodiversity.

Case study: East Walworth Green Links

Created by the 'friends of the park' groups, as part of Southwark's 'Living Streets' programme, the East Walworth Green Links project provides an alternative way of travelling between six parks from The Elephant & Castle to Burgess Park, linking the smaller parks on the way. For those on foot or bike, and the wildlife, the green link offers safety, quietness, greenery, cleaner air and relaxed travel.

Each of the parks provide a unique set of functions and variety of uses such as play areas and picnic spots, a pavilion and café, sports areas, pitches, courts and community sports centre, tennis courts, BMX track, outdoor gyms, youth shelters, and a viewing hill. There are memorial spaces and peace gardens for reflection and contemplation, as well as a history trail to aid interpretation of the cultural heritage of the area.

The Green Link provides a range of habitats, such as meadow, native and mature trees, rain gardens and water features, nature garden, semi-wild areas with fruiting and native species, relaxed maintenance wildlife areas, world plant borders, as well as community orchard and vegetable gardens.

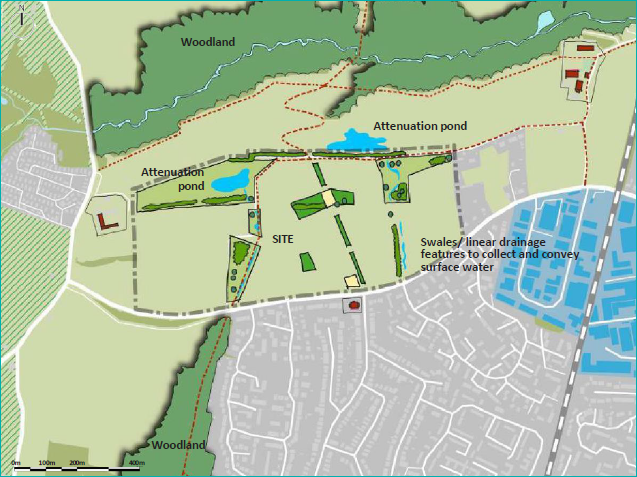

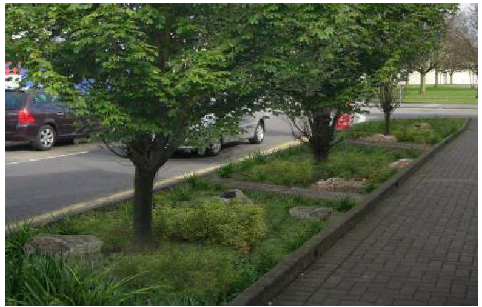

Principle DES12: Water features and sustainable drainage systems

Water features and Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) are an important element of public realm and should be incorporated into site structure from the outset. Where possible, existing watercourses and other surface water features should be used as a framework for the site layout and SuDS design, incorporated in accessible and central locations.

Site constraints should be considered and where woodland and/ or root protection zones are present, SuDS should be relocated to a more suitable area of the development. Evidence should be provided that any change to the water table does not adversely affect ancient woodland or ancient and veteran trees.

SuDS should not only enhance rainwater management, but provide improvements in water quality, visual amenity, reinforce the overall character of a site and enhance biodiversity. Above ground SuDS components should aim to create new habitats based on ecological context and site conditions. Areas of wet scrub and woodland, usually around larger detention and retention ponds and wet grassland can benefit a range of wildlife. SuDS features are likely to have greater species diversity if existing habitats are within dispersal distance for plants, invertebrates and amphibians.

SuDS should be designed with longevity and easy maintenance in mind and applicants should provide a management plan for their SuDS. Applicants are encouraged to use the SuDS guidance and pre-application advice service to identify any issues and risks from the outset.

A variety of SuDS mechanisms should be implemented on site, following the SuDS management train where control at source is preferable.

Figure 4.3: INDICATIVE SITE CONCEPT PLAN 3

A sustainable drainage network incorporated within open spaces is proposed through the site. These are strategically located to:

- Manage extreme rainfall/ cloudburst events, reducing pressure on conventional drainage systems and preventing pollution events

- Maximise the benefits of existing green infrastructure

- Provide additional visual amenity, biodiversity and enhance character of the new development

Storm water raingardens can be incorporated within the street design to attenuate rainwater

Reason

4.1.15 Sustainable drainage and watercourses are efficient ways of managing water run-off from hard surfaces by reducing the stress put on conventional sewer systems during high rainfall events, therefore reducing the risk of flooding. The choice of materials, the balance between soft and hard landscape areas and the use of green roofs, rain chains, rain gardens, swales and attenuation ponds are important elements in drainage design that should be incorporated into developments.

4.1.16 SuDS should be designed to avoid engineered appearance and respond to natural context. These systems can provide resilience to climate change and make significant contributions to improvements in landscape character, biodiversity, water quality, local identity and can increase aesthetic value.

SuDS feature integrated within the streetscene in Upton, Northampton

4.1.17 Applicants should follow a rigorous process when preparing flooding and SuDS proposals:

- Pre-app consultation and initial guidance Gotocouncil website;

- Refer to existing guidance for major and minor applications (Lead Local Flood Authority);

- Desk study and site survey;

- Informed intelligent layouts;

- Integration of water features at the beginning, not driven by developable plot areas;

- Define ordinary watercourse and buffers, which in most cases are required by VALP policy NE2 to be 10m between the top of the watercourse bank and the development;

- De-culverting requires land ownership consent; and

- Consult with relevant bodies and authorities where applicable, including the Internal Drainage Board and the Canal and River Trust.

Pond on Walton Grove, Aylesbury provides focal point and attractive setting for adjacent houses

Attenuation pond is poorly integrated into the residential development so that it has limited visual amenity value

Principle DES13: Design to enhance biodiversity

The principle of 'bigger, better and more joined up' should be followed to establish a strong and connected natural environment to enhance biodiversity. Design of development should:

- Achieve net biodiversity gain as a minimum standard for all development (the minimum % of net gain to be in line with legislation);

- Avoid harm and protect designated habitats, protected species and other flora and fauna;

- Follow the mitigation hierarchy by avoiding possible negative impacts on biodiversity as far as possible; and

- Follow the guidance set out in the Buckinghamshire 'Biodiversity Accounting Supplementary Planning Document' on how to calculate development impacts on biodiversity.

Landscape features which add ecological or habitat value to a site should be retained and enhanced. Development must retain and avoid priority habitats. For all other habitats, where this is not feasible evidence should be provided and suitable mitigation and compensation should be proposed. Compensation should be the last resort and habitats created should reflect the local context using native species of local provenance whilst prioritising protected species. Development must promote site permeability for wildlife and avoid the fragmentation of wildlife corridors, incorporating features to encourage biodiversity

New habitats should help achieve the targets set out in the Buckinghamshire and Milton Keynes Biodiversity Action Plan and support protected species.

Reason

4.1.18 Green infrastructure is expected to positively contribute to the conservation, restoration, creation and enhancement of networks of biodiversity on a multi- functional landscape scale to maintain water-quality, manage inland flooding and enhance carbon storage, to deliver a more effective ecological network. Lawton's principle states that 'recovering wildlife will require more habitat; in better condition; in bigger patches that are more closely connected' (A Green Future: Our 25 Year Environment Plan to Improve the Environment), and this approach should be applied to Aylesbury Vale. Small, isolated patches of habitat are more vulnerable to climate change, pests and disease, therefore connecting smaller pockets of habitats will help to preserve wildlife and allow it to flourish. The impact of climate change means that connecting corridors are needed to help build up much needed resilience.

4.1.19 Native planted buffers should be created adjacent to existing woodland (25-100m) as well as 5-10m buffers being retained or created around hedgerows. Natural England best practice defines that buffers of at least 15m should be provided between development and ancient woodland and at least 5m from the edge of the outermost tree canopy if this is larger than fifteen times the tree's diameter. Buffers should consist of semi-natural habitats of woodland, scrub, grassland, heathland and wetland planting as appropriate to the local habitat types and species and avoiding SuDS unless they are outside root protection areas and don't affect the water table. Buffers should be dark corridors with no lighting where possible, or include lighting designed to reduce wildlife disturbance. Domestic gardens should not be placed within buffers.

4.1.20 Ponds and other water bodies should be integrated into designs and managed appropriately to enhance wildlife and biodiversity.

4.1.21 Species focussed design should incorporate features within the built environment such as mammal runs, integrated bird and bat bricks, hedgehog holes and bee bricks, and should be included within planning applications.

4.1.22 Design for wildlife should include species-rich lawns, living roofs and walls, above ground SuDS components, and plants for pollinators and birds (such as fruiting and berry species).

4.1.23 Naturalising and re-wilding green spaces through relaxed management provides for habitats, wildlife and reconnects people with nature

4.1.24 Information boards explaining the reasons and the benefits of the area to wildlife and the role these areas play in the wider green infrastructure network should be provide where appropriate.

4.1.24 Best practice guidance is provided by the Natural Environment Partnership 'Incorporating Biodiversity & Green Infrastructure into Development.'

Case study: Kingsbrook Aylesbury

The Kingsbrook development and its relationship with nature conservation, in partnership with the RSPB, shows how nature and housing can be better integrated. The development aims to provide 60% wildlife-friendly greenspace, excluding gardens, with new housing surrounded by ponds, parks, meadows, orchards and a nature reserve.

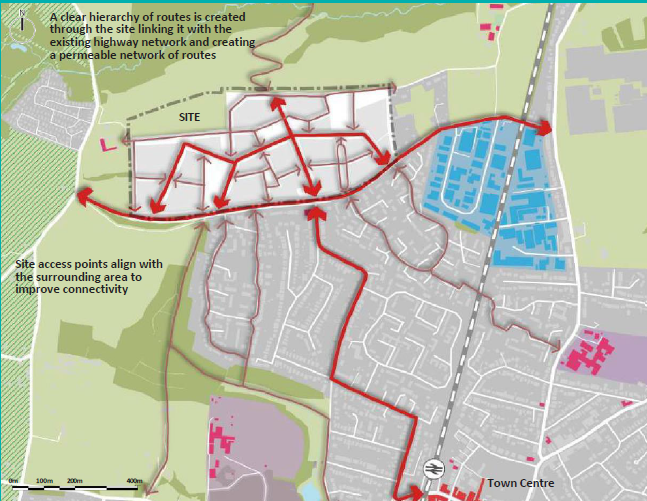

4.2 Movement network

Principle DES14: Establish a clear movement network that connects with the surrounding area

Applicants should design the layout of new development to:

- Link with existing routes and access points;

- Create direct, accessible, attractive and safe connections through the site for pedestrians, cyclists and vehicular modes which follow natural desire lines and connect to existing streets, open spaces, local facilities or destinations;

- Avoid turning heads by creating continuous vehicular routes around perimeter blocks;

- Carefully integrate public rights of way; and

- Respond to topography and landscape features; and

- Allow safe movement for wildlife and habitat connectivity.

The network should provide a choice of routes for all modes and follow a spatial and visual hierarchy, with the most direct routes reserved for sustainable modes in order to encourage use. The character of a street should reflect its position in this hierarchy and respond to local characteristics. Refer to Principles DES1-8)

While direct routes are most convenient, the design should also balance visual attraction, traffic calming and safety to optimise the pedestrians' and cyclists' experiences.

Applicants should avoid promoting developments that are accessed off a single location or promote long culs-de-sac that do not provide a choice of direct and convenient routes.

The opportunity should be taken to make pedestrian / cycle connections between adjacent development sites.

Figure 4.4: INDICATIVE SITE CONCEPT PLAN 4 - Establishing a clear movement network

Reason

4.2.1 Successful places are easy to get to, easy to move through and easy to find your way around. A connected network of streets offers choice, aids legibility, avoids turning heads and other engineered solutions and provides a hierarchy of street types which respond to the function and role of the street.

4.2.2 Development will need to adhere to the Highways technical advice as set out in the Highways Development Management Guidance on the council website. Go to council website

4.2.3 Developments should encourage sustainable lifestyles, minimise reliance on the car and provide choice to residents. This can have many benefits including improvements in health and well-being and to air quality. It needs to be planned early in the design process to provide space for alternative modes and to ensure that carriageway widths are sufficient.

4.2.4 Applicants should consider the needs of the most vulnerable road users first in accordance with the recommendations in Manual for Streets and Manual for Streets 2.

4.2.5 Development will need to adhere to the Highways Development Management Guidance and to CIHT Guidance on Buses in Urban Developments

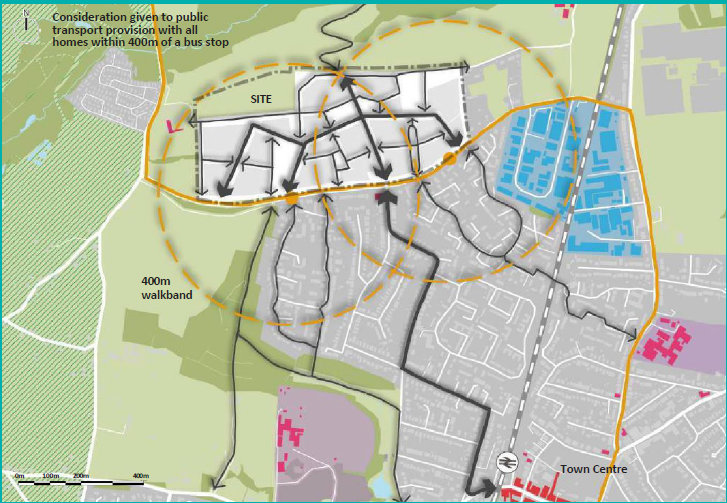

Figure 4.6: INDICATIVE SITE CONCEPT PLAN 5 - Accommodating public transport within the proposal

Principle DES15: Reduce reliance on the private car

Applicants should plan and lay out their development to minimise reliance on the private car. They should create a network of safe and convenient pedestrian and cycle routes that are attractive to use and that are integrated with the development and connect with the wider area and adjacent sites.

Public transport should also be accommodated where appropriate.

For larger developments (over 300 homes) applicants should consider at the outset how buses can be routed through a site and the provision of stops in the most accessible locations where they may serve both new and existing residents. This will inform consideration of street design at the more detailed design stage. Whenever possible new homes should be located within 300m (approximately 5 minutes walk) of a bus stop and with the distance between bus stops normally 200-400m.

|

Consider first Consider last |

Pedestrians |

|

Cyclists |

|

|

Publictransportusers |

|

|

Specialist service vehicles (eg emergency services, waste, etc) |

|

|

Other motor traffic |

Figure 4.7: User hierarchy from Manual for Streets

Figure 4.8: INDICATIVE SITE CONCEPT PLAN 6 - Scheme is laid out to allow for further development phases in the future

Principle DES16: Anticipate future development

The movement network / layout should be future proofed by providing streets that later phases of development can connect into at the edges of development sites.

This is typically achieved by a combination of:

- Legible links through the site; and

- Perimeter block layouts that generate roads around the perimeter of the site and building frontages that face the boundaries.

Reason

4.2.6 Much of the development built during the latter part of the 20th century is laid out as a network of culs de sac accessed off a distributor route and offering little potential for further expansion / extension at a later date. This reduces the potential to deliver well- connected sustainable development patterns and should be avoided.

4.2.7 Proposals should promote connections that extend to the edge of their land ownership allowing the potential for future development to be delivered in the longer term. These should be adopted as public highway to avoid creating future 'ransom strips'.

4.3 Existing townscape and heritage

Principle DES17: Respond to the existing townscape, heritage assets, historic landscapes and archaeology

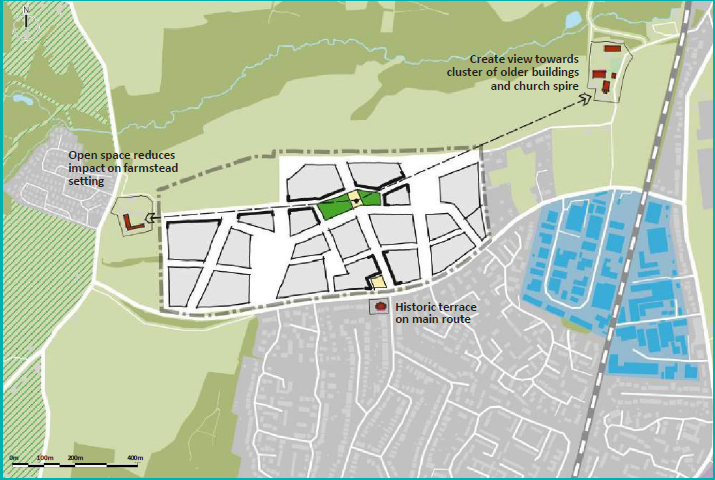

Heritage assets should be celebrated, enhanced or preserved, for peoples' enjoyment. Assets should be positively integrated into development to reinforce the existing sense of place and strong local identity and distinctiveness. Central to this process is understanding the significance of the asset(s) and using that understanding to guide development proposals and make informed design decisions.

Development should respect historic characteristics and assets on, and adjacent to, the site. An innovative and responsive approach to design is encouraged, creating an individual identity that complements or forms an attractive contrast with its surroundings. Quality of design and construction,

based on an understanding of site development, local characteristics and context, is key to ensure compatible design rather than a particular style or approach.

New development should respond to the physical context, including the pattern, scale and massing of existing settlements and the routes through and

around it. In larger scale developments there may be opportunity to create a new character that responds to the existing historic context. Important views should be respected, and new views created to add variety and texture to the setting and aid in embedding the proposed development in the surrounding context.

Figure 4.9: INDICATIVE SITE CONCEPT PLAN 7 - Scheme responding to existing townscape and heritage

Reason

4.3.1 Research undertaken in Heritage Counts, 2016, highlights the value of heritage as a source of identity, character, distinctiveness and sense of place. Heritage assets play an important part in peoples' perception and experience of place. Retained and enhanced heritage assets incorporated into developments conserve local identity and local distinctiveness.

4.3.2 Within Aylesbury Vale there is a wide variety of settlement types and contexts which is set out in Section 3.5 of this Design SPD. As highlighted in Chapter 3, local detailing and materials are an important part of identity. Commonly found within the Vale are red brick buildings with clay or slate roofs, as well as thatch, limestone or witchert walls, and occasional flint or rubble stone panels.

4.3.3 However, character is not driven by materials alone, and is a combination of interlinked elements. The combination of all elements: form, scale, massing, orientation, layout, roof form and detailing are important in providing character. New developments should respond to their historic character and setting, reinforcing it to create a sense of place which is appropriate to the context. It is expected that materials and building methods used in new development will be high quality, fit for purpose, and designed to weather and age appropriately.

4.3.4 Well-designed public art and interpretation panels are an effective way of communicating history and telling the story of place and should be appropriately integrated into the public realm.

Understanding significance to create better places

4.3.5 As part of the site appraisal (Principle DES8), applicants should have identified the heritage assets and historic character of the site and its surroundings. The character study (Principle DES7) should analyse the historical development of the site and identify the features that make the site locally distinctive. The next step is to make an assessment of significance of the heritage asset(s) involved.

Definition of significance (NPPF)

4.3.6 The concept of significance is central to the historic environment sections of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), where it is defined as, "the value of a heritage asset to this and future generations because of its heritage interest" (MCHLG 2021, NPPF p71). Value can take many forms, and a place or asset might tell us about the lives of people of the past, or be a fine example of artistic endeavour, or evoke an emotional response because of a connection with an event or person. Find out more about heritage values in Conservation Principles (Historic England 2008).

Why we assess significance

4.3.7 The purpose of protection and conservation measures for heritage assets is to sustain their significance. Understanding significance early in the process enables designers to respond positively to heritage assets and their settings, establishing a firm structure and enhancing the sense of place.

4.3.8 Documenting this understanding provides certainty for all those involved in the decision- making process, resulting in better quality and timely decisions. An assessment of significance is a statutory requirement for any application affecting heritage assets or their settings (Ibid. para. 189).

How to assess significance, what the report should contain

4.3.9 A statement of heritage significance should set out what is important about the asset, and why. It should take an impartial standpoint, rather than trying to justify proposals – this being the reason why it should be carried out before development proposals are formed. It also allows the assessor to identify the sensitivity of the asset, helping understand where change can be accommodated without adversely affecting special interest and also identifying where there is potential for enhancement of significance.

4.3.10 The assessment should be carried out by a suitably-qualified professional, or group of professionals in the case of a complex or multi-asset site.

4.3.11 Detailed advice about the content and process of carrying out an assessment of heritage significance is contained in Historic England 2019, Statements of Heritage Significance: Analysing Significance in Heritage Assets, Historic England Advice Note 12 - known as HEAN12 and Historic England 2015, Managing Significance in Decision-Taking in the Historic Environment: Historic Environment Good Practice Advice in Planning 2.

Relationship of Heritage Statements, Design and Access Statements and Impact Assessment

4.3.12 The statement of heritage significance can strongly support a Design and Access Statement, where one is required, as they both help to show how the applicant has appraised the context of the development and used this information in forming their design.

4.3.13 Design and response to context should be an iterative process; as designs develop, their impact can be checked against the baseline information established early on, and the design influenced further by this consideration.

4.3.14 A heritage impact assessment, based on the assessment of significance, will form part of the later stages of design development and submission of an application. There should be a hierarchy shown through the impact assessment, with adverse impacts avoided or minimised first, and only then mitigation measures provided for any remaining, unavoidable impacts. "Assessing significance before a proposal is planned can lead to better outcomes for the applicant by influencing the design by mitigating harmful impacts on significance, enhancing significance where possible, and thereby showing how any remaining harm is justified" (HEAN 12, para.7, p4).Case study: Alconbury Weald, Huntingdon

Case study: Alconbury Weald, Huntingdon

A large part of the Alconbury Weald development is located on the former RAF Alconbury airfield which was occupied from 1938 to 1995. The historic fabric of the site remains in the form of five designated heritage assets including hangars, a 13th Century manor house, control centres, bunkers and huts, reflecting a complex and fascinating history. The site also includes areas of historic farmland and a scheduled ancient monument in Prestley Wood.

The former airfield, with eleven miles of perimeter fencing currently sits within the surrounding area but is not part of it.

The development of Alconbury Weald provides an opportunity to reintegrate this land into the surrounding environment.

The proposed development weaves the historic significance of the site, and details, alignments, structures and historical events into the fabric of the development, in turn integrating the development into the historic environment around it. The approach is to:

- Retain, conserve, re-use and interpret the site's designated heritage assets;

- Propose green settings for the listed assets;

- Preserve and archive artefacts, records and drawings related to the site's buildings and use; and

- Develop community history and archaeology projects which will create public involvement in the protection of the site's heritage significance.

The main developer created a place making strategy and Design Code which provided a framework for development across the site, seeking to establish a real sense of place in this mixed-use neighbourhood.

References

Historic England 2008, Conservation Principles, Policies and Guidance. Go to Historic England website.

Historic England 2019, Statements of Heritage Significance: Analysing Significance in Heritage Assets, Historic England Advice Note 12. Go to Historic England website

Historic England 2015, Managing Significance in Decision-Taking in the Historic Environment: Historic Environment Good Practice Advice in Planning 2. Go to Historic England website

Heritage designations

Listed buildings

4.3.15 There are over 3,000 listed buildings in the Vale. The protection afforded by listing applies to the whole building and includes the interior and any curtilage structure within the grounds. Advice on determining whether a curtilage structure is listed can be found in Historic England's Listed buildings and curtilage advice note.

4.3.16 A listed building must not be demolished, altered, converted or extended in any way that would affect its character as being of special architectural or historic interest, without first obtaining listed building consent from the Local Planning Authority. Repairs, such as those which are not like-for-like or those involving the replacement of structural elements or historic fabric, often need consent and so applicants are encouraged to seek advice from the council's heritage specialists. In addition to listed building consent, planning permission and building regulations may be required.

4.3.17 Once a listed building consent application has been submitted, the Council will advertise the proposal and will require consultation with local amenity societies and parish councils for their views on the proposal. On minor works to listed buildings, the Council makes a decision when it has considered representations, and the process is normally completed within eight weeks. Applications for works to Grade I and Grade II* listed buildings as well as demolitions for all grades will also require consultation with various national bodies so will take longer to determine.

Deterioration of listed buildings

4.3.18 Listed buildings may, for a variety of reasons, fall into disrepair. Under such circumstances the Council has special powers. The Council can serve either a Repairs Notice or an Urgent Works Notice. Either Notice served on the owner specifies the works which are considered necessary to protect the building.

Setting of listed buildings

4.3.19 The Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 requires Local Authorities to have special regard to preserving the setting of listed buildings. The setting can include development at some distance, especially if the listed building forms a visually important element in the street scene or countryside. Development which affects the setting of a listed building requires careful appraisal. Advice on setting issues and how to assess changes to setting can be found in the Historic England publication 'setting of heritage assets'.

Guidance on submitting applications for listed building consent

4.3.20 Any applications that affect a Listed Building or conservation area will require a location plan, all floor plans existing and proposed, any external and internal elevations affected by the works and cross sections through the floor, roof, walls, windows, doors and ground level, where these are affected by the works. A Design and Access Statement should also be submitted, as well as photographs, perspectives or photomontages, models or computer visualisations, landscape works and phasing.

4.3.21 Refer to council guidance on validation requirements. A Heritage Statement will also be required as part of the application. In addition, there needs to be an indication that the implications of compliance with the relevant building regulations have been considered and accommodated in any scheme. The Conservation Management Plan provides best practice for converting listed buildings. National best practice, high level guidance and guidance for repairs is available from Historic England and Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB).

Conservation areas

4.3.22 There are 83 conservation areas in the Vale. Development within or adjacent to a conservation area must respect the special character of the area. Designs for proposals including extensions, windows and doors, boundary features, garages and parking, building materials, satellite dishes, renewable energy technologies, shopfronts, and advertisements will need to follow design guidance for conservation areas.

4.3.23 Further guidance can be found in AVDC Conservation Area Character Appraisals and the AVDC Conservation Management Plan. The Conservation Management Plan provides best practice for development within conservation areas. National best practice, high level guidance and guidance for repairs is available from Historic England and Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB).

Scheduled monuments

4.3.24 There are 61 scheduled monuments in the Vale. Scheduled monuments are designated for their national importance under the 1953 Historic Buildings and Ancient Monuments Act. Any works affecting a scheduled monument require scheduled monument consent (SMC) and their setting and special interest must be taken into account in any planning application affecting them. Further information can be found on the Historic England website.

Registered Parks and Gardens

4.3.25 There are 9 Registered Parks and Gardens in the Vale. The Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest, established in 1983, identifies landscapes of national interest and their designation gives them equal policy status with listed buildings and scheduled monuments. Their setting and special interest must be taken into account in any planning application affecting them. Further information can be found on the Historic England website.

Non-designated heritage assets

4.3.26 There are many other older buildings and areas which display a special character within Aylesbury Vale which do not reach the standards required for listing or designation on a national scale, but nevertheless have local interest and value. These non-designated heritage assets are recognised in National Planning Policy and deserve the care and respect that other heritage assets demand. Contact should be made with council heritage officers in order to determine if a building is a non- designated asset. An advice note on non-designated heritage assets in the Vale is available at on the council website. Go to council website

How to use

This table provides a checklist for use by both the applicant and planning officer to check that appropriate consideration has been given to how an application has established the structure of the proposal.

PROCESS: Have you read, understood and applied the principles set out through Chapter 4?

Have these principles been considered in conjunction with the Planning Designations, Character Study and Site Appraisal prepared in Response to the Site and Setting in Chapter 3?

The adjacent table summarises the key principles set out within this section and can be used by applicants and officers as a checklist.

Applicants will be expected to demonstrate to the council that they have responding adequately to all relevant principles in preparing their proposals, or provide a justification for any failure to do so.

|

PRINCIPLE |

DESCRIPTION |

CHECK |

|

DES9: Natural resources |

Has the design proposal used the physical characteristics of the site identified in Chapter 3 to influence the form and layout of new development? |

|

|

DES10: Topography and strategic views |

Does the design work with the topography and integrate the buildings within the landscape? |

|

|

DES11: Green infrastructure network |

Has the proposal responded to the site resources and indicated how these inform a landscape strategy? |

|

|

DES12: Waterfeatures and SuDS |

Where applicable has the design sought to retain, enhance and/or re-establish surface water features identified in Section 3 as positive features? |

|

|

Has the design incorporated the use of sustainable drainage as an integral part of the layout and landscape structure? |

||

|

DES13: Ecology and biodiversity |

Have landscape features with high biodiversity value identified in Chapter3 been retained and incorporated within the proposals? Has the mitigation hierarchy been followed? |

|

|

Do the proposals deliver measurable net biodiversity gain? |

||

|

Have new habitats been created or established, or existing habitats been enhanced or restored? |

||

|

DES14: Connect with the existing |

Does the proposal integrate with existing routes and access points, and create direct and attractive connections through the site for pedestrians, cyclists and vehicular modes? |

|

|

Does the movement network respond to topography and landscape features, and integrate new and existing public rights of way? |

||

|

DES15: Reduce the reliance on the car |

Does the proposal prioritise the needs of the most vulnerable road users first creating an attractive network of safe and convenient pedestrian and cycle routes? |

|

|

Does the proposal incorporate space for public transport where appropriate? |

||

|

DES17: Anticipate future development |

Is the design future proofed by providing streets that later phases of development can connect into at the edge? |

|

|

DES17: Heritage assets and the historic landscape / archaeology |

Does the design respond to, celebrate, enhance or preserve any heritage assets and historic landscapes within, or adjacent to, the proposals? |