Aylesbury Vale Area Design Supplementary Planning Document

7. Development in the countryside

7.1 Responding to the landscape

Principle DES51: Respond to the landscape character and setting

Applicants should demonstrate how the landscape character has been considered from the outset of the design process as an integral part of their proposal (refer to Principle DES2). This will be an important requirement within the Design and Access Statement.

Buildings within rural and lower density areas within the Vale should be simply integrated into their setting to be at one with the landscape.

Applicants must understand and respond to the particular characteristics of their site (refer to Principle DES8: Site Appraisal).

As a general rule, buildings should not be located on ridgelines or exposed sites where the buildings will become a dominant visual feature to the detriment of the existing landscape character.

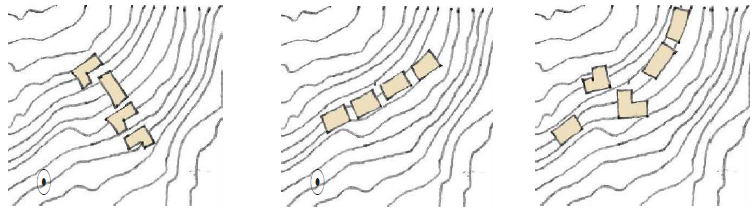

Development proposals should work with the topography. Integrating buildings around the existing topography can help to soften the appearance of a new development within the landscape. The topography of the site can also be used to provide natural shelter from wind and therefore prevent heat loss in winter.

Buildings on sloping sites should respond to the topography avoiding deep plan buildings and responding to the contours of the landscape rather than cutting across them.

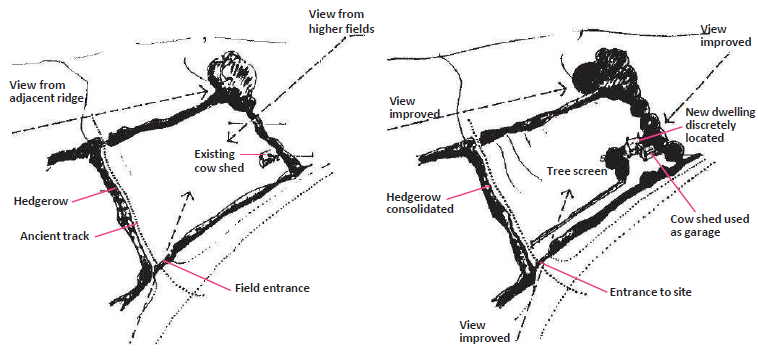

Applicants should retain important landscape features, mature trees and planting wherever possible and incorporate these features into the landscape structure.

Sufficient space should be allowed around new buildings and consideration must be given to the relationship of buildings with their boundaries on all sides.

Landscape elements, tree planting, and boundary treatments should be used to establish the building within the landscape, visually anchoring the building to its landscape setting.

Reason

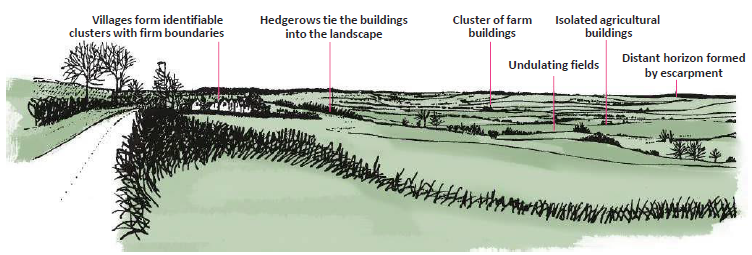

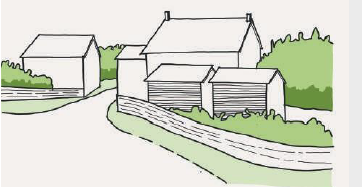

7.1.1 The countryside of Aylesbury Vale, away from the built-up area of Aylesbury is typified by a varied, rolling landscape. The escarpment of the Chiltern ridge provides a distant horizon whilst the lower hills, some with wooded crests, give an intermediate scale. Pockets of old woodland survive. Villages are mostly well-defined and form identifiable clusters seen from a distance, often with a church tower giving a focus to their overall composition. Farm complexes also form smaller building clusters dotting through the landscape

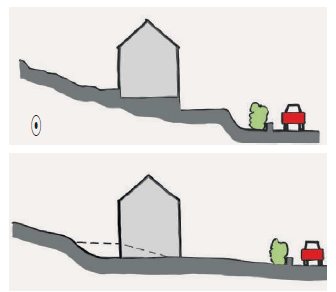

Figure 7.1: Buildings should not be located on ridgelines or exposed sites and instead should integrate into their setting

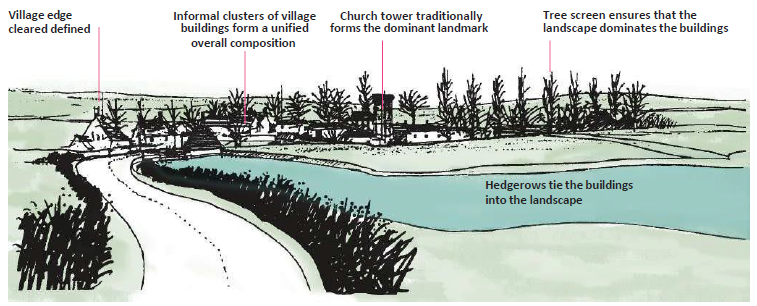

Figure 7.2: Typical form of a village, set within the landscape, in Aylesbury Vale

Figure 7.3: The characteristics of the Aylesbury Vale landscape

7.1.2 The landscape is given form and pattern by the network of fields and boundaries. Walls, hedgerows and trees tie the elements of the landscape together. Natural shapes and irregular patterns give a strong visual structure at all scales. Panoramic views see these elements knitted together across the landscape. Distant landmarks give scale. Country roads give a constantly evolving sequence of spaces and forms. Winding roads are complemented by mature trees which give punctuation and emphasis.

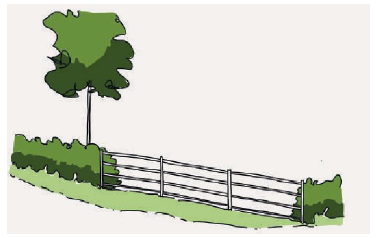

7.1.3 In all the views near and far across the countryside the treatment of boundaries is fundamental to their character. As well as defining the broader scale of the landscape, field boundaries emphasise the curves of country roads. They also provide the setting for buildings in the countryside. Most established development is seen over a boundary, so that the buildings are given a base, visually anchored to their landscape setting. Their setting may be further complemented by tree planting, either in groups or single specimens.

7.1.4 This relationship between the landscape, and the dwellings within it, is important and gives the area its rural character and charm.

7.1.5 Whilst one can point to examples of prominent eighteenth and nineteenth century country houses within the Vale that stand proudly in the landscape as dominant features these tend to be the exceptions.

7.1.6 Country houses have a unique relationship with their landscape setting; their exceptional architectural and generally planned formal landscape settings are unique elements within the landscape and not the typical relationship between built form and the landscape.

Figure 7.4: Understanding a site is critical to developing appropriate proposals

Figure 7.5: Proposals on hillsides should avoid development set at one level to avoid buildings 'merging' together, which is generally out of character in rural locations

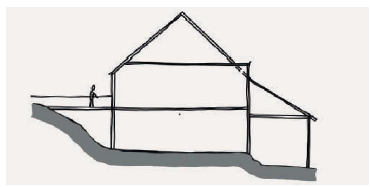

LEFT Figure 7.6: Buildings on sloping sites should avoid exposed plinths within the hillside and use the topography to the developments’ advantage. Building along the contours of the landscape rather than cutting across them can reduce this issue. RIGHT Figure 7.7: Building responds to the sloping site

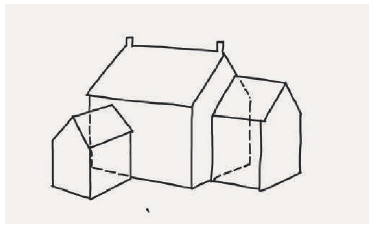

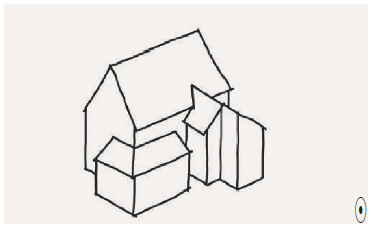

Figure 7.8: Traditional farm complex that has grown organically keeping the farmhouse as the dominant feature

Figure 7.9: Setting property back from boundaries allows tree planting

Figure 7.9: Setting property back from boundaries allows tree planting

Figure 7.10: Space between buildings is inadequate

Figure 7.13: Property has a good relationship with the landscape

Figure 7.13: Property has a good relationship with the landscape

7.2 Building design in rural areas

Principle DES52: Residential buildings in the countryside

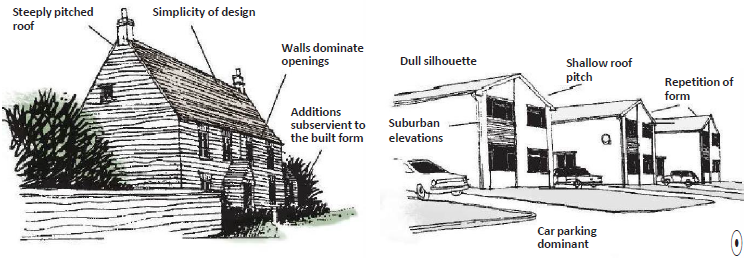

The majority of traditional buildings in Aylesbury Vale, in both urban and rural areas, adopt a very consistent, simple form, with rectangular floorplans and pitched roofs. In most instances new development should adopt a similar approach unless a reasoned justification or a strong architectural approach can be demonstrated.

Larger footprint buildings can often appear bulky and should be broken down to create a number of simple geometric forms.

Development heights should be responsive to their context and predominant heights within the area. The majority of development within rural areas in the Vale is one or two storey in height. Development that exceeds these will require strong justifications.

In rural areas buildings can often be seen from many locations within the wider area. As such it is important to understand the appearance of the building as a whole rather than having specific public and private facades. Building materials should respond to the context as set out in Principles DES4, DES6 and DES39.

Where groups of buildings are proposed these should mimic the organic forms of traditional village settlements with buildings clustered around a central space.

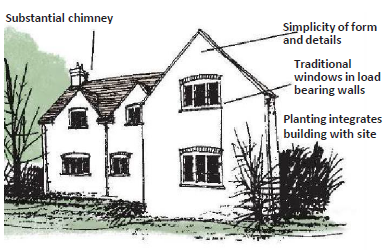

Left: Figure 7.14: Traditional property in village. Right: Figure 7.15: Traditional rural property

Reason

7.2.1 New buildings in the countryside should be designed so that they fit comfortably in the landscape and respond to context.

7.2.2 Individual houses should have a simple form which may be based on a rectangular plan and have a pitched roof with a central ridge. This basic form may be extended and added-to. Carefully placed ‘additions’ can enhance the overall composition. Simple forms are the key to success.

7.2.3 Traditionally houses were rarely built over two stories in height. The upper story often used part of the attic with ‘A’ framed trusses. This kept the ridge height down making for a more compact and efficient building that hugged the landscape and established

the tradition of countryside building.

7.2.4 Thatched and tiled roofs have pitches of at least 40 degrees to ensure efficient dispersal of rainwater. The introduction of slate allowed pitches to be reduced to 30 degrees although these can appear squat from a distance. In all but special circumstances 40 degrees should remain the normal roof pitch. Unequal main pitches should be avoided.

7.2.5 Local building traditions often include low eaves lines and extended roofs. This helps to bring new buildings down in scale and relate them to their sites.

Left: Figure 7.16: Simple building form with sympathetic additions. Centre: Figure 7.17: Form of additions create awkward interfaces with elevations and roof. Right: Figure 7.18: Building with twin roofs helps to reduce the impression of the overall bulk. However a central valley gutter is created which needs careful detailing.

LEFT Figure 7.19: Deep plan buildings can appear too bulky in proportion and out of scale with the countryside. RIGHT Figure 7.20: Groups of buildings in a cluster mimic the organic forms of traditional village settlements.

LEFT Figure 7.22: Extended roof forms help the building to blend into the landscape. RIGHT Figure 7.21: Garages in rural areas should be designed to look like outbuildings.

Principle DES53: Rural boundary treatments

The front boundary of a site should be defined by either walls, timber post and rail fencing, railings and/or hedges and trees to reflect the general character of the immediate area. Close board fencing will not be acceptable.

Front gardens should be provided with lawns, tree planting, hedges and only small areas of hard surfacing, either gravel or paving.

Trees and hedgerows, especially along property boundaries should be retained wherever possible. If trees and hedges do need to be removed, they should be replaced within the site.

Reason

7.2.6 The interface and boundary treatment of plots and the street / country lane and surrounding areas should be reflective of the character of the area as identified in the Applicants Character Study.

7.2.7 The Vale's rural areas are generally characterised by the landscape and mature trees, hedgerows and planting are important to their character and setting. These landscape elements in combination with walls, timber post and rail fencing and railings form the boundary and definition of individual plots.

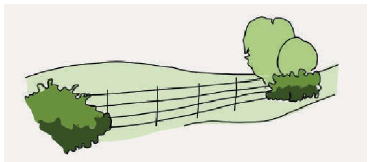

Left: Figure 7.23: Timber post and rail fencing is a traditional boundary treatment. Centre: Figure 7.24: Steel railings combine well with hedgerows and are traditionally used as estate boundaries. Right: Figure 7.25: Bricks, especially a local type, can form a very strong boundary wall. Walls should not appear over-dominant and look better if associated with planting.

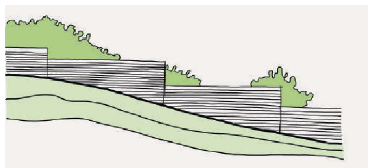

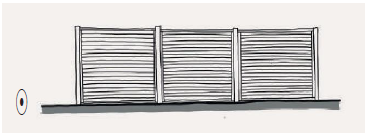

Top: Figure 7.26: Over-elaborate and ostentatious entrances are generally out of place in the countryside. Centre: Figure 7.27: Decorative railings are usually too suburban to suit the open landscape. Right: Figure 7.28: Close-boarded fencing can form a barrier obscuring open views. It is hard to detail satisfactorily and is prone to wind damage on exposed sites

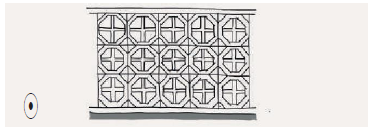

Figure 7.29: Precast concrete blocks are too geometric for countryside use. They impose a rigid pattern of too small a scale which does not accord with the rise and fall of field boundaries

Principle DES54: Agricultural and equestrian buildings and infrastructure

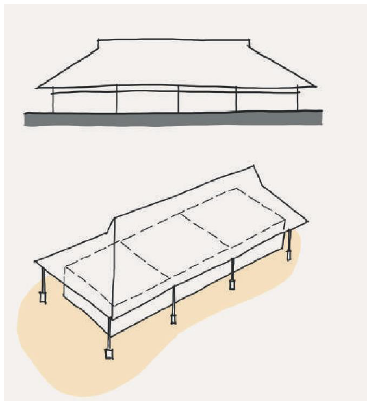

Where agricultural, equestrian or other non- residential buildings or infrastructure are proposed within rural settings care must be given to how they respond to their landscape setting in order to avoid buildings or infrastructure that are dominant on views and / or unsympathetic to their landscape setting.

Consideration must be given to:

- The location on the site to minimise visual impact;

- The building form with traditional forms that follow traditional barn design preferred;

- Building with traditional materials e.g. clay tiles or slate preferred to roofing felt on roofs, and weatherboarding or brick for walls. Materials should be in muted colours and tones to reduce visual impact;

- The use of vegetation and structural planting (using native species) to act as a visual screen where appropriate;

- The use of lighting, proposals should aim to minimise impact and light spill to surrounding areas.

Left: Figure 7.30: Stables and riding schools have become established throughout the countryside. The use may be strongly related to its context but often the associated buildings and paraphernalia clutter up the landscape with unsuitable forms. Right: Figure 7.31: Large buildings could follow traditional barn design

Left: Figure 7.30: Stables and riding schools have become established throughout the countryside. The use may be strongly related to its context but often the associated buildings and paraphernalia clutter up the landscape with unsuitable forms. Right: Figure 7.31: Large buildings could follow traditional barn design

Reason

7.2.8 In recent years there has been a proliferation of larger buildings, often associated with equestrian activities, but also related to sports facilities (e.g. club houses or pavilions) being promoted in the Vale. Whilst these may serve a community function they can have significant visual impact and are often not sympathetic to the character of the area.

7.2.9 Infrastructure in the form of solar farms, water treatment works or roads and railways can have a significant impact on the rural setting and must be carefully planned to minimise this impact.

How to use

This table provides a checklist for use by both the applicant and planning officer to check that appropriate consideration has been given to the design of development in the countryside.

PROCESS: Have you read, understood and applied the principles set our above?

The adjacent table summarises the key principles set out within this section and can be used by applicant and officer as a checklist.

Applicants will be expected to demonstrate to the council that they have responding adequately to all relevant principles in preparing their proposals, or provide a justification for any failure to do so.

|

PRINCIPLE |

DESCRIPTION |

CHECK |

|

DES51: Respond to the landscape character and setting |

Has the applicant demonstrated that they understand and have responded to landscape character and to the characteristics of their site including to topography, trees and existing boundaries? |

|

|

DES52: Residential buildings in the countryside |

Does the scale, form and massing of the building and the materials used respond to local character? Has the applicant considered how the development will appear from all directions? |

|

|

DES53: Rural boundary treatments |

Does the definition of site boundaries respond to the character of the immediate area? Are existing trees and hedgerows retained? |

|

|

DES54: Agricultural and equestrian buildings and infrastructure |

Do agricultural, equestrian or other non-residential buildings or infrastructure respond to their landscape setting so that they do not over dominate views or present an unsympathetic response to their landscape setting? |

|

|

Has consideration been given to the location to minimize visual impact, use of traditional materials , use of structural planting or vegetation to act as visual screening and / or use of lighting to minimise impact or light spill? |