Aylesbury Vale Area Design Supplementary Planning Document

6. High quality and sustainable building design

6.1 Deliver sense of place

Principle DES37: Promote high quality buildings that respond to their location and deliver a sense of place

Applicants should promote high quality buildings that provide a positive interface with street space, are designed from high quality robust materials and that respond to their location within the area. The council welcomes innovative and inventive design solutions and adaptable buildings that can accommodate changing lifestyles, including providing for an aging population and that challenge standard house types or development models.

Scale, height and massing

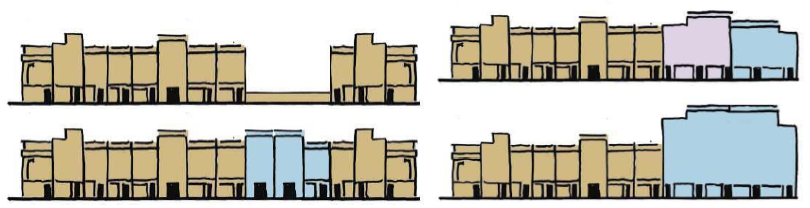

The scale of new buildings should relate to their context (rural or urban), their location within the hierarchy of routes and whether they act as a focal point, landmark or corner building and the topography of a site.

Subtle variations in height can be used to add visual interest. This can be achieved with differing ridge and eaves heights, as commonly found in traditional streets. Similarly, variations in frontage widths and plan forms can add further interest to the street scene. This can be appropriate in both urban and rural locations.

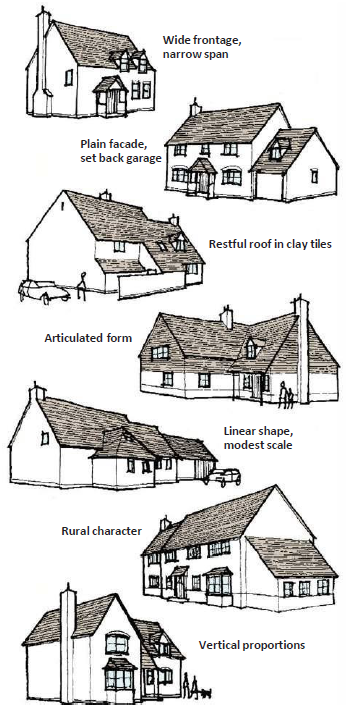

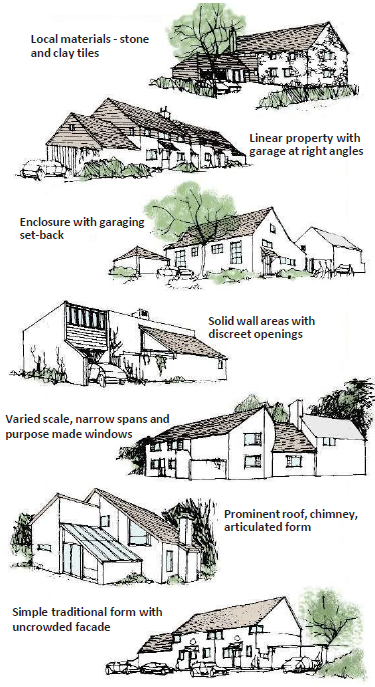

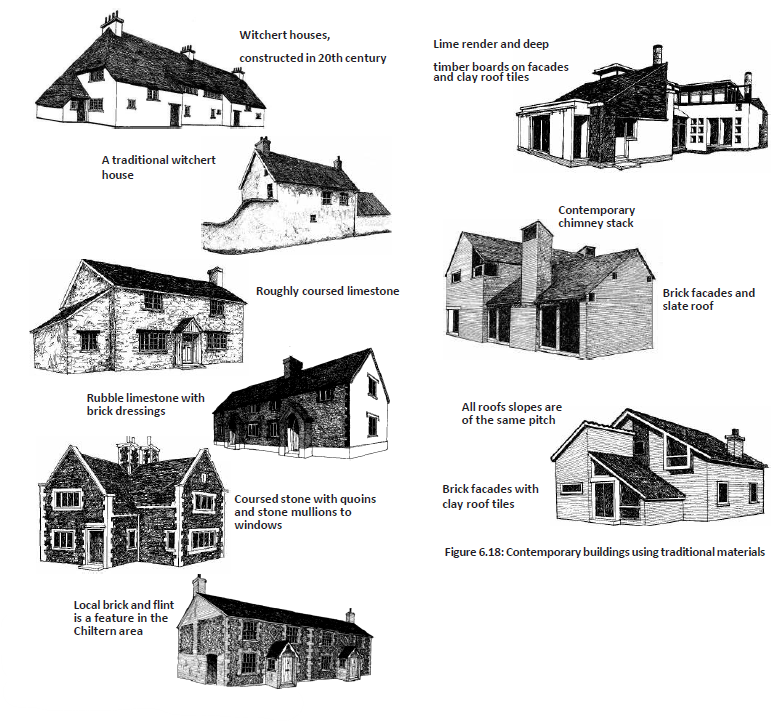

The majority of traditional buildings in Aylesbury Vale, in both urban and rural areas, adopt a very consistent, simple form, with rectangular floorplans and pitched roofs over narrow spans. In most instances new development should adopt this simple form, with a rectangular floorplan and pitched roof unless a strong justification can be provided. Good contemporary design that respects context will be welcomed as long as it is well designed; equally traditional design approaches may be acceptable where a good understanding of materials and proportions is demonstrated. Poor pastiche approaches that aim to mimic historic vernacular but that are inappropriately proportioned, poorly detailed and fail to incorporate local materials will not be acceptable.

Corner buildings

Particular attention should be given to corner buildings (those located on the intersection of two streets). These buildings should be designed so that they 'turn the corner' providing active frontages to both streets; 'L' shaped buildings maintaining continuity of built frontage and incorporating corner windows and entrances will be welcomed in these locations.

Applicants should demonstrate how the design of corner buildings will aid legibility. Exposed, blank gable ends with no windows fronting the public realm will not be acceptable.

Apartment buildings

Corner locations are often suitable for apartment buildings where additional height may be appropriate to mark the corner. This will however depend on the character and context of the site. Apartment buildings will be welcomed on town centre sites, neighbourhood hubs, adjacent to important spaces or landscapes, nodal points, corners or the junction of major routes.

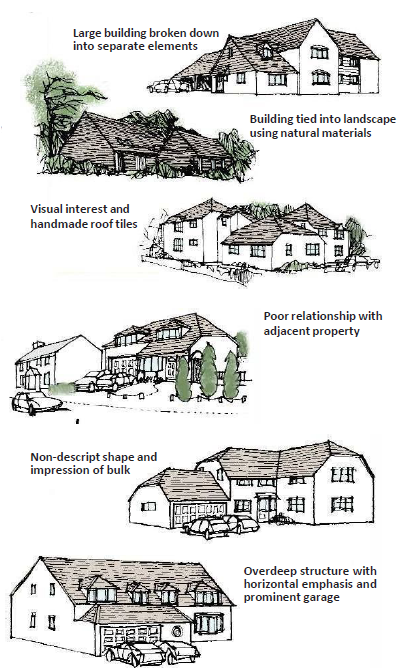

Apartment buildings may be deeper in floorplan than houses and as such care should be taken to avoid buildings appearing bulky. These larger buildings should be broken down into a hierarchy of simple rectangular elements and should step down adjacent to lower scale buildings.

Such buildings must maintain active street frontages with ground floor flats or duplex units having their own front doors and doors to lobbies / stairwells, used to access upper floors, also helping to activate frontages.

Single aspect, north facing apartments will not normally be acceptable.

Contemporary design examples that respond appropriately to rural (left and bottom right) and urban contexts (top right)

These homes are a parody on the historic forms that they imitate with a scale, proportions and design detailing that fail to achieve a contextual response

Reason

6.1.1 Many of Aylesbury Vale's towns and villages retain an attractive historic core which provides a strong character and sense of place. Many are designated as conservation areas reflecting the historic character. Development proposals should demonstrate an understanding of their historic context to build upon and reinforce the distinctiveness of their site and wider area.

6.1.2 Post-war development within the Vale is of mixed quality. In many cases it neither responds to local character or delivers distinctive or interesting contemporary accommodation that provides for the needs of modern living.

6.1.3 Whilst some recent developments offer good contemporary interpretations of the traditional building forms many developments rely on a pastiche design approach that present poor interpretations of the past and unsuccessfully imitate vernacular designs; typically they get the dimensions and scale of features wrong, over-simplify details or use inappropriate materials to save cost. This parody of the historic building forms sits uncomfortably within the context of the Vale and fails to offer a contemporary response to the changing lifestyles and accommodation requirements.

Scale and massing

6.1.4 The use of local materials and historical construction techniques are largely responsible for the simple forms of traditional buildings in the District. In general, traditional houses in the area have a distinctly rural character, pitched roofs over narrow spans,

and employ a limited range of materials. Sensitive interpretation of these characteristics is a preferred option for new development in a traditional context.

Figure 6.1: The majority of traditional buildings in Aylesbury Vale adopt a simple form, with rectangular floorplans and pitched roofs. Development should take cues from the prevailing forms within the context to strengthen local character

6.1.5 Articulation of roofs and building form and a response to the surrounding built and landscape context enhances the quality and sense of place.

6.1.6 Buildings that are poorly proportioned or fail to respond to the scale and massing of adjacent properties have an adverse impact on their setting.

Figure 6.2: Applicants should assess the prevailing scale, form and massing of successful development within the locality to inform their proposals

6.1.7 In town centre locations and within larger residential proposals apartment buildings may be appropriate provided that their scale and massing, and articulation of detail, responds to the sites context.

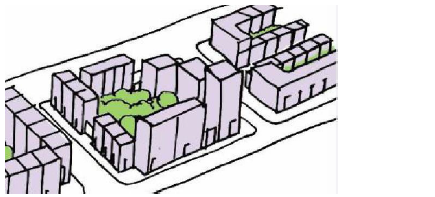

Figure 6.3 (RIGHT): Development should reflect the scale, grain and diversity of the existing settlement. Figure 6.4 (LEFT): Apartment buildings should respond to the scale, massing and grain of the context in a complementary way and avoid becoming overbearing

Figure 6.5 (Left): Apartments should be proposed at appropriate locations within urban areas and add to the legibility of an area

Addressing corners

Figure 6.6: Gable ends which incorporate windows provide overlooking

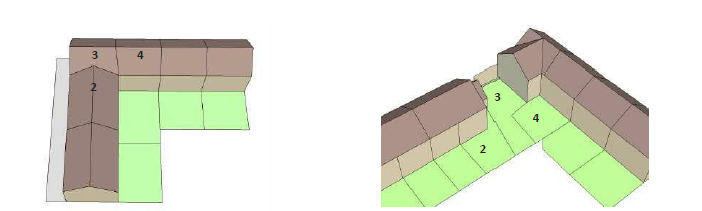

Left: Figure 6.7- Linking houses together at a corner causes problems with garden space and privacy. Here the example shows there is no garden for houses 2, 3 and 4. Right: Figure 6.8 - By extending plot 3 to turn the corner and setting back plot 2 it provides sufficient space for a garden. By providing plot 2 with a single storey element and an adjoining brick wall, it further assists with maintaining a built frontage

Principle DES38: Promote buildings that respond to and help to enclose and animate the street space

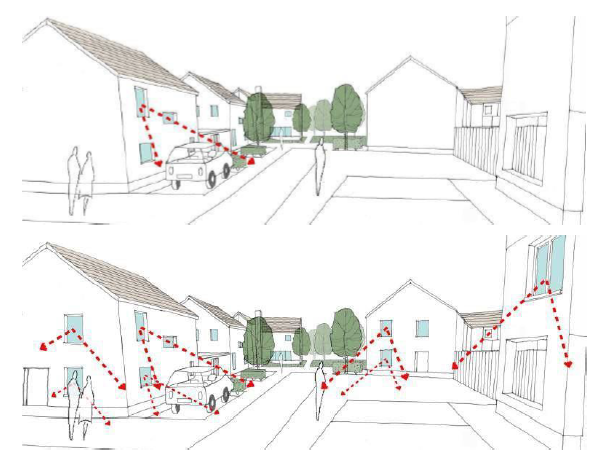

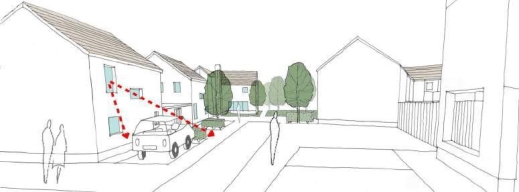

Development should be designed to ensure that urban streets and public spaces have good levels of natural surveillance from buildings. This can be achieved by ensuring that in urban areas, streets and spaces are overlooked by ground floor habitable rooms and upper floor windows.

Apartment buildings within town centre locations should generally have non- residential uses at ground floor level and these should be designed to provide an 'active' frontage to the street. The floor to ceiling height at ground floor level should be greater to allow flexibility on its future use.

Apartment buildings that do not incorporate ground floor non-residential uses should be designed to avoid bedrooms at the ground floor level overlooking the public realm as this can reduce privacy for residents and also reduce passive surveillance of the public realm. It is often more appropriate to incorporate duplex units on the ground and first floor of apartment buildings to avoid such scenarios.

Boundary treatments

In town or village centre locations or mews style developments, buildings may be located directly to the rear of the footway or public realm, but in most cases properties should have a boundary that defines public and private space including front gardens.

Boundary treatments should be reflective of the area and local traditions in terms of height, structure and materials. This should be drawn from the applicants Character Study (refer to Section 3). Boundary treatments should not impair natural surveillance or wildlife movement.

For larger developments boundary treatments should be coordinated to contribute to the character of the street but allow for some variety and individuality.

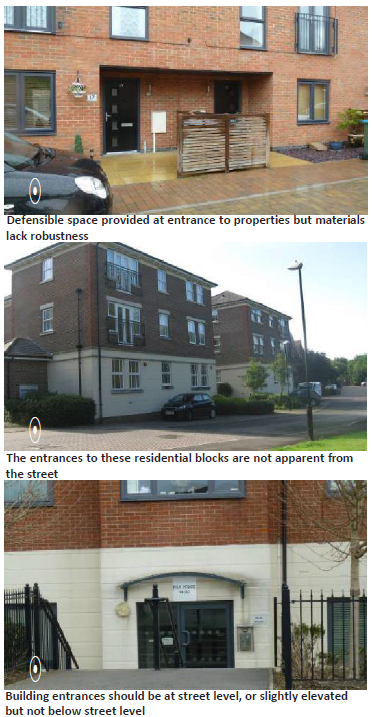

Building entrances

Main entrances to houses, ground floor flats, communal entrances for flats and non residential uses should directly face onto the street and be clearly visible from the public realm.

All building entrances should be welcoming and easily identifiable to help improve legibility.

The scale and style of an entrance should relate to its function. The more important the function of the building, the more impressive the entrance should be. For example, a public building should have a larger and more prominent entrance than a house.

Recessed entrances or canopies integrated into the design of the building facade should be provided whilst avoiding creating areas that are hidden from view. Canopies should not appear to be 'bolt-on' solutions and instead make a positive contribution to the building facade.

For apartment buildings entrances to shared stair cores should be directly from the street and should be generously proportioned, well lit by natural light and naturally ventilated.

Ground floor dwellings within apartments should have individual entrances direct from the street. This increases the animation of the public realm and reduces the numbers of dwellings served by communal cores.

Overlooking the street

Figure 6.9: Ensuring that all public areas are overlooked by adjacent buildings, to increase ‘eyes on the street’ will reduce the likelihood of anti-social behaviour

Boundary treatments and building entrances

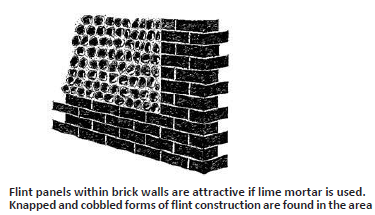

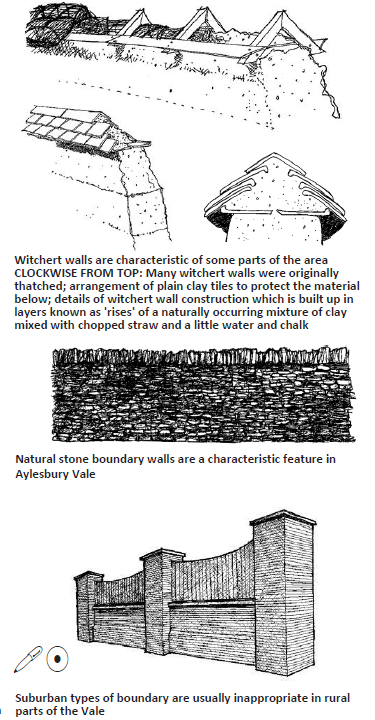

6.1.8 The interface of a property with the public realm should be clearly defined in a manner that responds to or complements that used in the local area. In some areas boundaries are predominantly defined using brick walls sometimes in combination with flint; in others the prevailing material is stone or witchert. Generally walls should have proper coping details and avoid 'brick on edge'. Native species hedging, estate railings or post and rail fences are also acceptable in rural areas.

6.1.9 Access gaps should be left to allow wildlife to move. For example, 13cm holes cut into wooden or concrete fences, holes dug under obstacles, or ramps used over low walls, allow hedgehogs to roam safely and breed successfully

6.1.10 Suburban types of boundaries including metal railings, reconstituted stone walls and brick walls in combination with timber fencing, can look out of place in a rural setting and should be avoided. Equally the use of timber knee rails and bollards should be avoided. Both should generally be unnecessary if a design is properly thought through

Figure 6.10 (Left): Entrances to important buildings, apartments and non-residential uses should be more civic in their appearance. Figure 6.11 (Above): Entrances to dwellings should have a more domestic scale to them

6.2 Architectural integrity

Principle DES39: Promote buildings that have architectural integrity utilising high quality detailing and materials

Applicants should establish an architectural approach and identity borne from the place in the design of building.

The facade and elevational treatment, roofscape fenestration and materials used in existing buildings within the locality should be a starting point for the consideration of architectural design of new buildings. However this should not result in poor pastiche replicas that present a parody of traditional buildings. Instead a re-interpretation of key aspects of their form should be demonstrated; for instance, their symmetrical layout, window to wall ratio, and proportions and placement of windows and doors.

The architectural approach must consider

- Elevational treatment and façade design;

- A choice of window design that is determined by the overall design approach;

- A simple roofscape and form that creates a harmonious composition and minimises the visual impact of downpipes and guttering;

- Incorporation of dormer windows informed by the character and appearance of the local vernacular;

- A contemporary interpretation of traditional chimneys (where appropriate); and

- A context appropriate palette of good quality materials, with a preference for local materials and/or materials with low embodied energy. The durability and resistance to weathering of materials is an important consideration in selection.

Reason

6.2.1 New development in Aylesbury Vale must respond to the characteristics of the place. Applicants should refer to their Character Study (refer to Chapter 3) to understand distinctive features and characteristics of the area and re-interpret this in their proposals.

It is particularly important to reflect the historic characteristics of conservation areas and other heritage assets within or in the context of the site in this

Facade and elevations

6.2.2 Applicants should refer to their Character Study (refer to Section 3) to consider the facade and elevational treatment of existing buildings within the locality and this should be a starting point for the consideration of elevational treatment and facade design for new buildings.

6.2.3 The area has a wide range of architectural styles and the arrangement of building facades varies however they are usually simply organised with windows and doors aligned both horizontally and vertically.

6.2.4 Applicants should avoid crowded façades and arrangements that are almost, but not quite, aligned.

6.2.5 Particular care must be taken with the:

- Choice of materials to respond to place and allow for future maintenance. Applicants should promote a consistent treatment to the front and rear facade and avoid the use of render;

- Design of balconies to ensure that they are integrated into the design and do not appear as 'bolt- on' or dominant features;

- Integration of rainwater downpipes;

- Location of meter boxes to ensure that they are inconspicuous

Windows

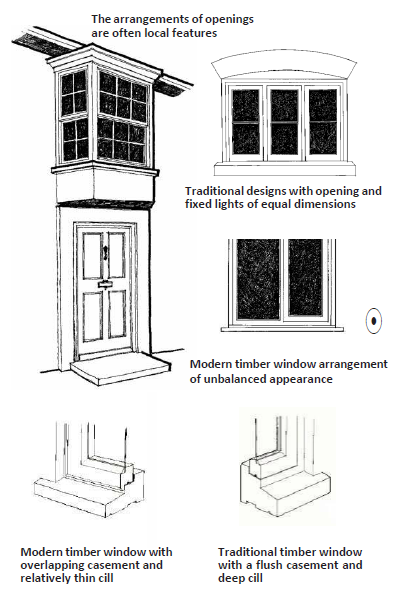

6.2.6 The choice of window design should be determined by the overall design approach. For example, a contemporary design may incorporate large glazed elevations, which would be inappropriate in a more traditional design. The number of window openings and their size can have a profound effect on the appearance of a building.

6.2.6 The choice of window design should be determined by the overall design approach. For example, a contemporary design may incorporate large glazed elevations, which would be inappropriate in a more traditional design. The number of window openings and their size can have a profound effect on the appearance of a building.

6.2.7 With careful design, windows can create a light and airy impression and make a building appear less bulky. However, if poorly designed, too many windows can make a building appear overly fussy and fail to respect the character of the area. It should also be noted that a greater window area will increase the energy demands of a building.

6.2.8 Buildings of traditional design should predominantly have rectangular windows, usually constructed of timber, with the emphasis on either the horizontal or vertical axis. Modern buildings can have a variety of window designs provided they are part of an overall design concept.

6.2.9 The positioning of windows, including sill and arch/lintel heights, needs careful consideration to ensure the design reflects the character of the area. In more traditional designs, the positioning of windows within their reveals is also important – windows that finish flush with the front face of a building can appear flat and uninteresting, whereas windows that are set back within reveals cast shadows which add visual interest. The degree of any window recess should also take into account the choice of facing material. For example, stone buildings can accommodate a deeper window recess than brick buildings.

6.2.10 Bay windows can be used to add interest to elevations and create attractive features on buildings.

6.2.11 UPVC windows are less successful in design terms, particularly in traditional buildings and historic settings due to their bulky frames and glazing bars. Wherever possible, timber should be used unless an alterative material is shown to be more appropriate.

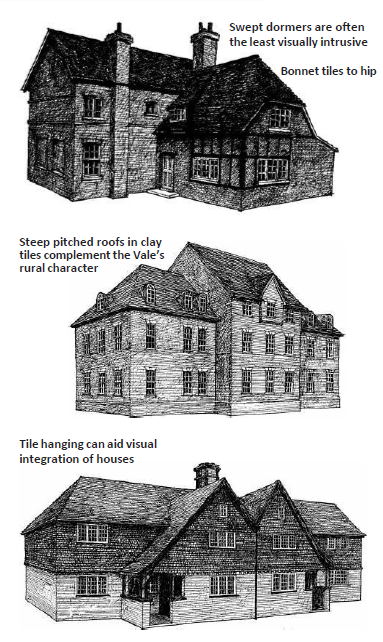

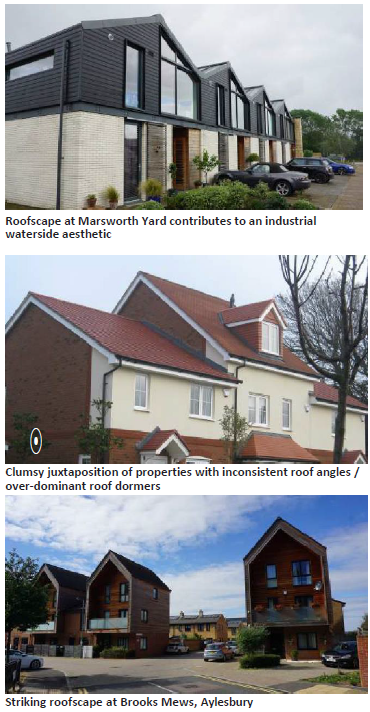

Roofscape

6.2.12 The pitch and form of roofs and the roofscape within a settlement are important to the character of the place.

6.2.13 Applicants should refer to their Character Study (refer to Section 3) to consider the prevailing roofscape within the locality.

6.2.14 In Aylesbury Vale, the use of steep dual pitched roofs in clay plain tiles is predominant on older buildings. Slate and clay pantiles are also widespread roof materials. There are also a considerable number of thatched buildings. New development should respect these simple characteristics.

6.2.15 Plain clay tiles are preferred for roofs, where roofs are hipped, then bonnet hip tiles are preferred for hip ridges as this gives a complete and harmonious appearance to the roof as a whole. "Handmade", that is, irregular clay tiles which match earlier products, may be required for Listed Buildings or in Conservation Areas. Machine made clay tiles are generally less suitable than "handmade", but these are preferred to concrete tiles. Plain tiles are always preferable to concrete interlocking tiles by virtue of their size and lapped arrangement.

6.2.16 Materials used for roofs are associated with different roof pitches (refer to section 3.6). Where there is a prevalent angle of pitch within a settlement this

can be a powerful contributor to the character of the area. Applicants should consider if this is the case and whether this should be reflected within their proposals.

6.2.17 Proposals should avoid shallow pitched roof profiles or inconsistent roof angles juxtaposed towards each other.

Chimneys

6.2.18 Chimneys are a traditional feature within Aylesbury Vale which contribute to the character of the area. Developments are encouraged to include chimneys as they can contribute to the overall appearance of a development.

6.2.19 Chimneys or stack features can be used in modern ways such as for thermal stacks to aid ventilation in summer, to incorporate flues from wood burning stoves or as a service core for gas flues or vent outlets.

6.2.20 Chimneys can be located in a number of positions including:

- On the gable end or projecting from the gable end, usually at first or sometimes second floor level;

- Along a side or rear wall or occasionally on the front;

- Within the gable end;

- Along the ridge;

- Projecting from the roof plane away from the ridge; or

- A central position within the building optimises energy efficiency as there is less heat loss than if located on an external wall.

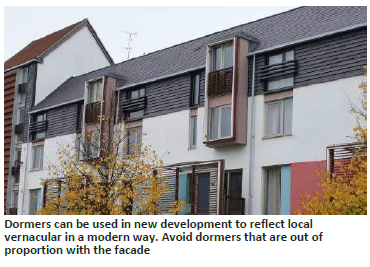

Dormers and rooflights

Dormers and rooflights

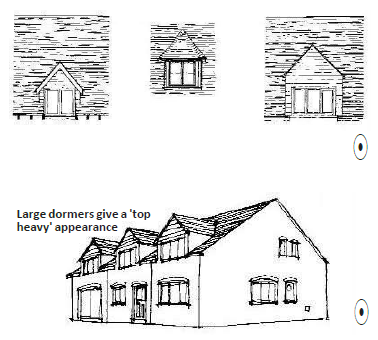

6.2.21 Dormer windows can be prominent traditional features in the streetscene. However, care needs to be taken with their design, proportions and position on the roof. Large horizontally proportioned dormers appear top heavy and alien to traditional form.

6.2.22 The choice of design should be informed by the character and appearance of the local vernacular.

6.2.23 Dormers should be positioned so that they line up with openings on the main façade.

6.2.24 Rooflights may be a discordant element on new houses unless they are small, positioned out of public view or used sparingly. Flush fitting rooflights, that use non-reflective glass can reduce the visual impact of roof openings.

Figure 6.15: Dormers are an acceptable feature on the roofscape but must be carefully positioned and proportioned so that they do not dominate or unbalance the architectural composition

Garages

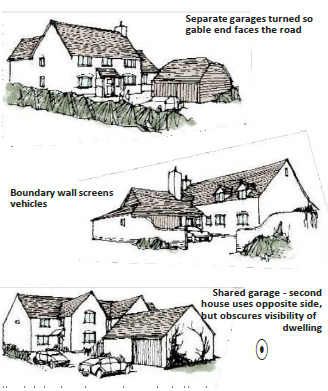

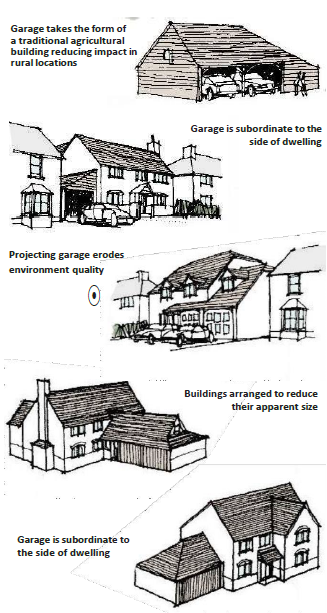

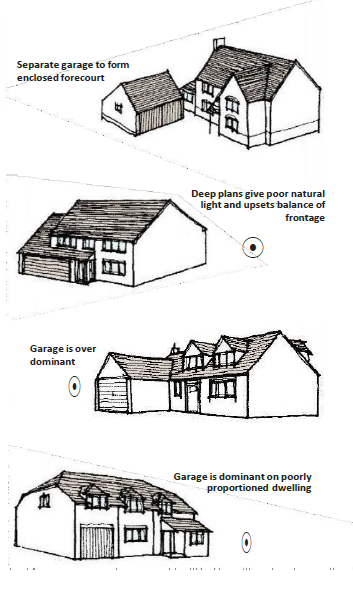

6.2.25 The front door is traditionally the main feature of a house, a point of focus and entry. Garage doors can however be the largest single element on a house elevation and when inappropriately located can over dominate and create an impression of the dwelling being subordinate.

6.2.26 Garages must be carefully sited and proportioned so that they are subordinate to the main dwelling and not visually prominent.

Figure 6.16: The design of garages and their relationship with a dwelling must be carefully considered

Materials

6.2.27 Whilst architectural style varies within the area a prevailing characteristic of most successful buildings is a simple, restrained palette of materials, detailing and architectural features integral to the design.

6.2.27 Whilst architectural style varies within the area a prevailing characteristic of most successful buildings is a simple, restrained palette of materials, detailing and architectural features integral to the design.

6.2.28 The choice of materials and architectural features in new development is often overly complicated, pastiche or includes 'bolt-on' elements that are out of place.

6.2.29 The choice of materials and detailing should be drawn from the local context and re-interpreted if a contemporary approach is taken.

6.2.30 Materials should reflect the character of the area and also the style of architecture adopted. For instance, for a traditional architectural approach use the materials that are used within the area (eg for roofs normally plain clay tiles or slates) where as if a contemporary approach is taken there is potential to explore a wider range of materials (eg zinc / copper roofing).

Principle DES40: Consider the location and design of utility meters and rainwater goods so that they don't adversely impact the quality of development

Utility meters should be carefully planned for so that they are both conveniently located and unobtrusive.

Enclosures for utility services and meters must not dominate the building frontage and solutions must be harmonious with the overall architectural design of the property.

Wherever possible, rainwater goods, external service pipes and other apparatus should be grouped together and discretely located on elevations which are not prominent. This requires careful consideration of the provision of all services at the initial design stage. Service routes beyond properties should be carefully planned so that they do not impact on existing trees or the potential for new trees. Refer also to Principle DES32.

Apartment buildings should always have a communal aerial and satellite dish if cable TV is not available, and a condition should be attached to the planning permission to this effect.

Reason

6.2.31 The apparatus of modern services (e.g. external pipework, flues, vents, meter cupboards, satellite dishes and aerials) can create a cluttered appearance and detract from the design of an otherwise successful development. Careful consideration, therefore, needs to be given to their location, materials and integration on buildings.

6.3 Residential amenity and privacy

Principle DES41: New development must be designed to respect the privacy of existing residents

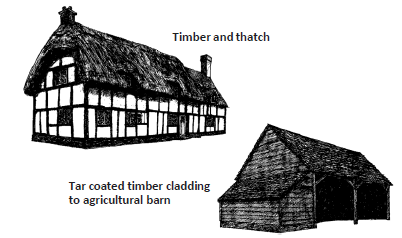

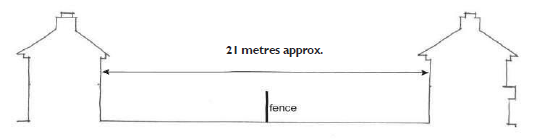

Applicants will need to demonstrate how privacy will be maintained between new and existing development whilst designing to the principles of compact neighbourhoods in more urban locations.

The relationship of buildings to each other, their height and the positioning of windows and the provision of good noise insulation can all have an impact on the privacy enjoyed by neighbouring properties. When providing more compact development applicants may consider positioning of windows or arrangement of habitable rooms to reduce direct views. This must also take account of changes of level / topography.

The use of set back upper floors, recessed balconies and internal courtyards can all help to deliver higher densities whilst respecting privacy.

Direct overlooking of private amenity space by habitable rooms in neighbouring properties should be avoided.

Reason

6.3.1 It is important that all residents are able to feel comfortable in their own home and an adequate level of privacy is required to assist this.

Figure 6.19: An adequate distance between facing habitable rooms helps enable people to feel comfortable in their own homes. Sometimes, through creative design, it is possible to reduce the back to back distances with other measures to avoid overlooking.

Principle DES42: Provide attractive and usable external amenity space for all homes

All dwellings should have access to private outdoor amenity space. This open space should be appropriate to both the location of the proposal and the type and size of accommodation and it should be located where it is not subject to continuous overshadowing.

Amenity space should be provided in the form of a private garden, patio, balcony or communal garden depending on the type of dwellings being provided. Private gardens should be treated as an extension of the living space of the house.

Communal gardens should be incorporated to the rear of blocks to provide visual amenity and outdoor space for residents. Soft landscaping should be prioritised over areas of hard standing and consideration should be given to provision of outdoor seating, eating, drying and growing space.

External access to gardens should be provided to allow for maintenance and removal of garden waste without passing through a property. Long, narrow alleyways should be avoided.

Increasing structural diversity by retaining and creating buffer areas of woodlands, species rich grassland, ponds or native plant hedgerows can all encourage wildlife.

Wildlife-friendly gardening and climate-resilient native species planting should be promoted. Bird and bat boxes, bee bricks and dead wood can create additional habitat. Native plants and wildlife also enhance soil fertility, increase pollination, and provide natural pest management.

Creating microclimates can protect gardens from climate-related weather extremes. Microclimates can be built throughout by taking advantage of retained natural features like shade trees, rocks, ponds and slopes.

Ground floor homes in apartment blocks should have access to a well defined, rear, private area. This will act as 'defensible space' and create good quality amenity.

Residents living in upper floor apartments should have access to outdoor spaces, which could include a balcony which is large enough to be enjoyed and a communal space to do activities not facilitated by balconies. Balconies should be positioned to ensure they do not cause overlooking of neighbouring properties.

Reason

6.3.2 Providing private amenity space in the form of garden space, balconies or communal gardens is important in achieving a successful and attractive

development.

Principle DES43: Homes should be designed to receive adequate daylight and sunlight and to avoid overshadowing

All properties must have access to adequate daylight and sunlight. Single aspect north facing apartments should be avoided as they do not gain direct light and single aspect south facing apartments are not generally welcomed as they are subject to overheating.

Within higher density developments care should be taken to avoid areas which are permanently in shade or overshadowed by adjacent buildings.

Buildings close to the boundary of neighbouring properties can increase overshadowing or loss of daylight to neighbouring properties.

Principle DES44: Design to minimise the impacts of noise, air and light pollution

Disturbance from noise, light sources and the impacts of poor air quality can be reduced through careful design. The following techniques can be used:

- Orientate buildings so that habitable rooms and sitting out areas do not face noise and light sources;

- Locate amenity areas including gardens, communal gardens, play areas and balconies away from areas of poor air quality;

- Introduce design features such as recessed balconies, acoustic lobbies and winter gardens;

- Construct barriers such as garages or walls between noise sources and dwellings;

- Use landscape to absorb noise and to improve air quality; and

- Locate noisy external activities such as play areas close enough to the properties they serve to be safe and usable but far enough way to avoid noise disturbance.

Reason

6.3.3 Noise can be a source of significant aggravation for residents, particularly at night. Issues associated with noise are particularly prevalent in locations close to external sources of noise such as railway lines and busy roads.

6.3.4 Air pollution is associated with a number of adverse health impacts; it is recognised as a contributing factor in the onset of heart disease and cancer. It particularly affects the most vulnerable in society: children and older people, and those with heart and lung conditions. Development must therefore be designed to minimise exposure to areas of poor air quality and to explore opportunities to mitigate the impacts through for instance planting.

6.4 Commercial buildings

Principle DES45: Commercial buildings

Employment buildings should respond positively to the character and architectural traditions of the area in terms of scale, mass, form, materials and detailing.

Within town centres offices must present a positive interface with the street with entrances prominent and helping to animate the street space.

On business parks and industrial estates as a general principle, the landscape and public realm should form the dominant feature within employment areas with the buildings forming a more neutral background. As such, the design of simple, rectilinear buildings within the landscape is promoted. Planting schemes for these areas should favour locally appropriate native species.

The design of commercial buildings must consider:

- Articulation of the ground floor of buildings to create a more human scale;

- More generous floor to ceiling heights typically between 4.0 and 4.5m;

- Consideration of building materials that are responsive to place. Where buildings are located within the countryside, materials should be in muted tones so that buildings blend in to the surrounding environment. Highly reflective materials should be avoided;

- The design of building entrances so that they are generous and welcoming, include covered areas and are easily identifiable to help improve legibility and provide protection from the weather;

- The location of reception areas and office space so that it positively contributes to the surveillance of entrance areas and forecourts; and

- The location and coordination of signage to minimise its impact and ensure that signage on buildings is not overbearing on the streetscape or out of proportion with the scale of buildings.

Whilst it is accepted that some employment buildings will be of a significant scale, applicants should consider the impact of these buildings on views from the countryside and the wider context. Measures to mitigate their impact should be considered. For example, low profile pitches / barrel vault roofs may be preferable to angular flat roofs. Green roofs should be considered where appropriate.

Reason

6.4.1 Well designed commercial buildings that are designed to respond to place and to animate and address streets will contribute to more attractive environment for people working in Aylesbury Vale and also to the image and perception of the place as a location to establish new businesses or relocate to. This could have significant economic benefits for the area.

6.5 Sustainable buildings

Principle DES46: Minimise environmental impact by energy efficient and sustainable design

Sustainability must be considered throughout the design process for all proposed developments, including retrofits and extensions, employing appropriate technology in energy generation, renewables, and low carbon energy. This should include use of sustainable materials.

Where possible, all developments are encouraged to achieve BREEAM 'Excellent' Standard

Electric vehicle infrastructure within all new developments should be provided in accordance with the latest standards, with consideration given to future requirements for the technology.

Applicants must demonstrate how sustainability has informed their design which should consider orientation and design of buildings to maximise daylight and sun penetration, whilst also avoiding overheating, and the use of:

- Green roofs or walls to reduce storm water run-off, increase soundproofing and biodiversity;

- Materials with low embodied energy or recycled materials (for example re-use of existing concrete as road fill or in foundations);

- Materials with a high thermal mass, such as stone or brick, which store heat and release it slowly;

- Photovoltaics or solar thermal water heating;

- Water efficiency;

- Ground or air source heat pumps for heating; and

- Low flow technology in water fittings, rainwater harvesting systems and grey water recycling systems to reduce water consumption.

Reason

6.5.1 The increasing realisation of the climate emergency means that the government is now committed to reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050. Investing in and implementing sustainable design practices will help to work towards climate mitigation, whilst improving economic growth and creating healthier communities.

6.5.2 The council's aspiration to deliver sustainable development and a resilient future should be reflected in all applicants' proposals.

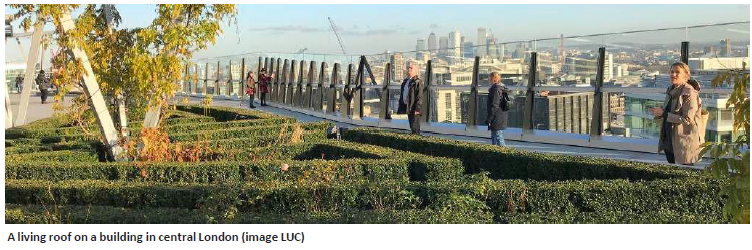

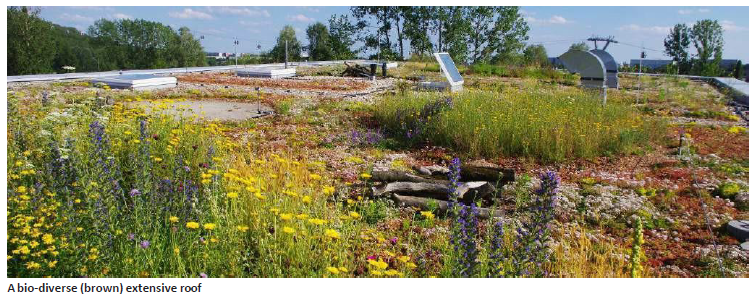

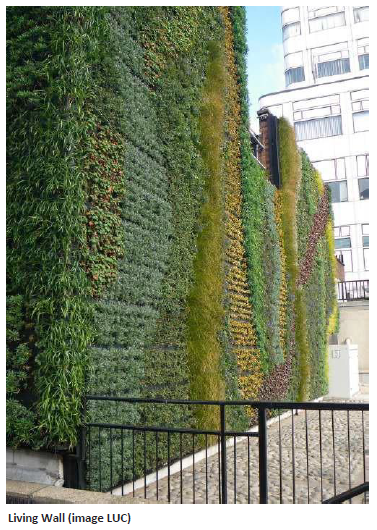

Principle DES47: Living roofs and walls

Living roofs and walls should be considered to improve sustainability of buildings: through managing water run-off, conserving and enhancing biodiversity in urban areas, increasing energy efficiency and visually integrating buildings into rural surroundings. Living roofs should be considered when proposing flat or shallow pitched roofs, including garages and extensions to buildings.

Careful consideration should be given to position, form and design, setting clear objectives to determine the best type of living roof or wall. Appropriate species selection and understanding and meeting maintenance objectives are vital for success.

Reason

6.5.3 Living roofs and walls are vegetated roofs and walls. Living roofs can take differing forms in order to maximise their benefits in a given location. Living roofs can be ‘green’ when a planting scheme is established on a roof structure, or ‘blue’ when the aim is to control and reduce rainwater run-off.

6.5.4 The main benefits include:

- Rainwater attenuation;

- Provision of wildlife habitat;

- Energy savings;

- Visual and landscape benefits;

- Improved air and water quality;

- Quieter buildings;

- Space for food production; and

- Reduced costs, including drainage, heating, air conditioning.

6.5.5 Living roofs can play an important role in the sustainable management of rainfall and surface run- off reducing the flow of water to the conventional sewer system, as part of a Sustainable Drainage System (SuDS). Their ability to retain water and slowly release it back to the system is an efficient method of source control. Light rainfall events (5mm or less) are normally completely absorbed by a green roof. Thorough waterproofing is a key consideration.

6.5.6 Living roofs and walls can also provide increased biodiversity, particularly within urban areas, forming part of the green infrastructure network and improving connectivity, further integrating habitats. With incoming requirements for Biodiversity Net Gain, biodiverse green roofs and species-rich green walls

are increasingly being used in urban areas to recreate habitat lost by development. As habitats on buildings tend to be isolated from ground level habitats, the most important wildlife associated with living roofs and walls

tend to be invertebrates, birds and bats.

6.5.7 Conventional roofing surfaces absorb sunlight and release radiation back into the atmosphere, further contributing to the urban heat island effect. A building that has poor insulation and poor ventilation can also lead to increased use of air conditioning and therefore increased energy use. The many layers of living roofs and walls and evaporation of water from soil surfaces and leaves can bring the dual benefit of limiting the impact of climate change by keeping areas cooler while at the same time reducing energy use and carbon dioxide emissions.

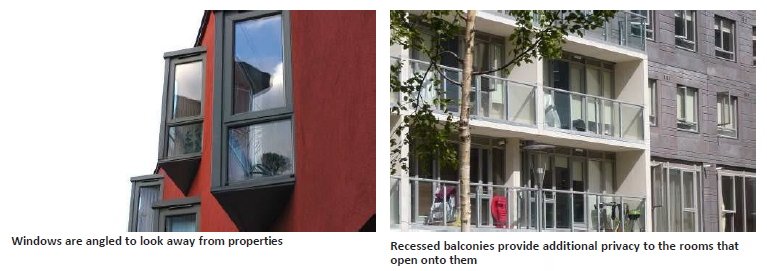

Intensive and extensive roofs

6.5.8 Green roofs can be broadly broken down into intensive or extensive systems.

6.5.9 Intensive systems are generally used as recreational spaces and often include similar features to traditional parks and gardens such as shrubs, trees, paving, lawns and even water features.

6.5.10 Extensive green roofs generally provide greater biodiversity interest than intensive roofs, but are less appropriate in providing amenity and recreation benefits. Extensive green roofs designed specifically to create habitats for plants and animals are known as biodiverse (or brown) roofs. They typically combine wildflower and meadow type vegetation with varied substrate topography and materials.

|

Extensive |

Intensive |

|

|

Use |

Ecological landscape |

Garden / park |

|

Type of vegetation |

Mosses, Herbs, Grasses |

Lawn, perennials, shrubs, trees |

|

Benefits |

Water, thermal, biodiversity |

Water, thermal, biodiversity, amenity |

|

Accessibility |

Not generally designed for public access |

Can be designed for limited or full public access or high visibility |

|

Substrate depth |

60 – 200mm |

150mm up to 1000mm |

|

Weight |

50-250 kg / m² |

>150 kg/m² up to 2000 kg/m² |

|

Maintenance costs |

Low (1-3 visits per year) |

High (regular visits) |

Figure 6.20: Table indicating the differences between extensive and intensive living roofs

6.5.11 Photovoltaic (PV) panels can be combined with green roofs and both systems will function as they should if designed correctly. Key issues to consider are spacing of the PV arrays, selection of shade tolerant plants and regular maintenance. These roofs are named 'solar' green roofs, if the PV panels are mounted on the green roof system or 'biosolar roofs' if the PV are integrated.

Living walls

6.5.12 Living walls are those covered in some form of vegetation. Whereas roofs are not always a visible feature, living walls can become a major design feature, in addition to providing benefits for biodiversity, thermal efficiency and amelioration of pollutants.

6.5.12 Living walls are those covered in some form of vegetation. Whereas roofs are not always a visible feature, living walls can become a major design feature, in addition to providing benefits for biodiversity, thermal efficiency and amelioration of pollutants.

6.5.13 Living walls can be separated into a number of categories:

- Supported by a wall e.g., self-supporting climbers;

- Supported by a structure on a wall e.g., trellis;

- Supported by a self-standing structure away from a wall;

- Hanging walls; and

- Walls with plants growing within them.

6.5.14 Living roofs and walls require appropriate levels of daylight, moisture, drainage, aeration to the plant's root systems, nutrients and maintenance. It is vital to know if the usual growing conditions of each species are comparable to the ones on the roof or wall to ensure their ability to adapt and flourish, as climatic conditions can often be extreme.

6.5.15 Well designed and constructed living roofs and walls will require structural engineers to calculate loading capacity of the roof, the heating and cooling implications and to integrate existing and proposed mechanical equipment and drainage needs. Landscape architects will be needed to design the layout of the planting areas and specify the planting. Health and safety consultants can advise on maintenance issues. Further design guidance can be sourced from the Green Roof Code of Best Practice incorporating Blue Roofs and BioSolar Applications.

Principle DES48: Sustainable building materials

Applicants should consider the use of sustainable materials to reduce the impact on the environment and provide a long-term durable solution for the built environment. This can range from technical solutions (for example, carbon fibre reinforced cement, lime mortars, wool insulation, recycled plastics, breathable paint) to socio-technical and economic (life cycle analysis and supply chain specification).

Developments should look to minimise construction waste, reuse and recycle. Locally sourced materials should be used, both reinforcing local character and reducing transport related impacts.

Materials which have a high thermal mass, such as brick and stone, are preferable, as well as the need for providing high levels of insulation.

Alongside sustainable building materials, sustainable building design, which allows for passive heating and cooling, is encouraged, see Principle DES46: Minimise environmental impact by energy efficient and sustainable design.

Reason

6.5.16 Sustainable buildings materials are those considered to not deplete non-renewable (natural) resources and to have no adverse impact on the environment when used. The following principles should be followed to preserve natural resources and reduce the impacts of the materials used in development.

6.5.17 Preserve natural resources by:

- Avoiding use of scarce (non-renewable) materials, such as weathered limestone.

- Creating less waste.

- Using less; by not over-specifying performance requirements, by designing minimum weight structures and by matching demand to supply (such as balancing cut and fill).

- Using reclaimed, rather than new materials.

- Using renewable materials (crops, such as thatching roofs, which also reinforces local vernacular).

6.5.18 The impact of materials can be reduced by:

- Using materials with low embodied energy.

- Reducing transport of materials and associated fuel, emissions and road congestion.

- Preventing waste going to landfill.

- Designing and constructing for ease of reuse and recycling at end-of-life (design for deconstruction).

6.5.19 Constructing with sustainable materials is better for the environment, can save money in the long term, help preserve our heritage, respond to planning policies and meet building standard requirements, such as BREEAM. Applicants are encouraged to use recycled materials or materials with a low-embodied energy. The full life-span of materials should also be considered, including their re-use potential once their purpose has been served.

6.5.20 Wherever possible, materials with a high thermal mass and which reflect the local character of the area should be used.

Principle DES49: Local energy production

Applicants should integrate energy efficient solutions and renewable energy production into developments.

Renewable energy is encouraged, however it should be designed and implemented taking into consideration impacts on:

- Landscape and biodiversity;

- Views;

- Historic environment;

- Green belt, particularly sense of openness;

- Aviation;

- Highways and access;

- Residential amenity; and

- Land use and agricultural quality.

6.5.21 Local energy production is essential for the building of resilient and sustainable communities, through methods which help to economically boost the area. Masterplanning should be undertaken in such a way as to optimise the sustainability of the development as a whole taking account of wider infrastructure, orientation of buildings and other issues.

6.5.22 Renewable energy technologies should be integrated with the design of a building from the outset and designed to be sympathetic to the context of the building, landscape and/ or heritage.

6.5.23 For residential developments over 100 dwellings, the feasibility for district heating via combined heat and power technologies should be explored and evaluated.

6.5.24 Sustainable construction issues should be included in pre-application discussions. Where a sustainable construction assessment of a proposed development is required, an assessor should be engaged at the earliest possible stage to provide the best balance between maximising the sustainability potential of the development and minimising costs.

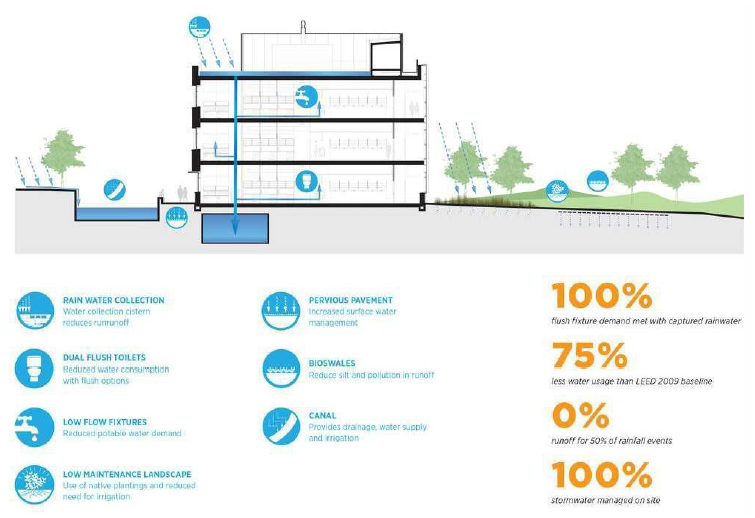

Principle DES50: Reducing water demand

Applicants should take steps to reduce water demand, waste and enhance efficiency. Water recycling, rainwater harvesting, and efficient appliances are all methods of achieving this. Refer also to Principle DES46: Minimise environmental impact through energy efficient and sustainable design and Principle DES47: Living roofs and walls.

Applicants should consult with either Anglian or Thames Water (whichever applies) to understand the position on water resources, with an overarching aim to reducing mains water consumption.

Where possible, the council encourages solutions for rainwater re-use to be explored as a priority before drainage solutions are then considered.

Reason

6.5.25 Aylesbury Vale sits within an area of water stress, and therefore high levels of water efficiency should be implemented and retrofitted into development, to provide adaptive measures to climate change.

6.5.26 VALP policy I5 requires all new homes to be built to the higher standard of water efficiency and re-use set out in the Building Regulations, which sets a maximum consumption of 110 litres per person per day.

Figure 6.21: Water cycle strategy

How to use

This table provides a checklist for use by both the applicant and planning officer to check that appropriate consideration has been given to the design of buildings within a proposal.

PROCESS: Have you read, understood and applied the principles set our above?

The adjacent table summarises the key principles set out within this section and can be used by applicant and officer as a checklist.

Applicants will be expected to demonstrate to the council that they have responding adequately to all relevant principles in preparing their proposals, or provide a justification for any failure to do so.

|

PRINCIPLE |

DESCRIPTION |

CHECK |

|

Response to character |

Do the proposals demonstrate a response to the character of the area as identified within the Character Study in Section 3? |

|

|

Response to constraints and opportunities |

Do the proposals demonstrate a response to the site constraints and opportunities as identified within the Site Appraisal in Section 3? |

|

|

DES37:Sense of place |

Does the design generally reflect or respond to the scale of the existing settlement and positively contribute to the character as identified in the Character Study in Section 3? If not has a strong justification been provided? |

|

|

Does the scheme incorporate variations in height responding to the location within the proposal, for instance reflecting the street hierarchy, enhancing legibility of an important corner or node or emphasising a particular use? |

||

|

Is the location of any apartment buildings appropriate and justified? |

||

|

Does the new development adopt a simple form in-keeping with the character of the area? If not is the reason justified? |

||

|

Do corner buildings 'turn the corner' providing frontage to both streets? |

||

|

Has the applicant demonstrated how the use of corner buildings has been considered in order to aid legibility? |

||

|

Does the scheme avoid exposed, blank gable ends with no windows fronting the public realm? |

||

|

DES38: Enclose and animate the street |

Does the development ensure that all streets and public spaces have good natural surveillance from buildings? |

|

|

Does the development clearly define public and private space through the use of appropriate boundary treatments? If not, is this justified? |

||

|

Are these boundary treatments reflective of the area as established in the Character Study? |

||

|

Are all property entrances directly onto and easily visible from the public realm? Are they legible and welcoming? |

||

|

If there are apartments within the scheme are their communal entrance cores generous, well lit by natural light and naturally ventilated? |

|

6.High quality and sustainable building design |

Checklist |

||||

|

PRINCIPLE |

DESCRIPTION |

CHECK |

|||

|

DG39: Architectural integrity |

Has the applicant demonstrated an architectural approach and identity borne from the place and reflected through the Character Study? |

||||

|

Is the choice of door and window design appropriate to the overall design approach? |

|||||

|

Does the roofscape proposed reflect the simple roof structures characteristic within the area? |

|||||

|

Are larger buildings broken up into a series of smaller spans or modules of a simple form to ensure the roof does not dominate the building or surrounding area? |

|||||

|

If chimneys are incorporated into the design are they reflective of the character of the area? |

|||||

|

If dormers are incorporated into the design are they reflective of the character of the area? |

|||||

|

Are they positioned to line up with openings on the main façade? |

|||||

|

If rooflights are proposed are they appropriately sized and positioned out of public view? |

|||||

|

Is the palette of materials and detailing proposed of high quality and reflective of the character of the area as established through the Character Study? |

|||||

|

DES40: Utility meters/external pipes |

Are utility meters located where they are both convenient and unobtrusive? |

||||

|

Are external service pipes / rainwater goods and other apparatus grouped together and discretely located on elevations so that they are not prominent? |

|||||

|

DES41: Privacy |

Does the design respect the privacy of existing residents in adjacent dwellings? |

||||

|

Does the design respect the privacy of future residents in the proposed development? |

|||||

|

DES42: Amenity |

Do the proposals provide attractive and usable external amenity space appropriate to the location of the proposal and the type and size of accommodation? |

||||

|

DES43: Daylight and sunlight |

Do all properties receive adequate daylight and sunlight? |

||||

|

Does the proposal avoid providing single aspect north facing apartments? |

|||||

|

Does the proposal minimise provision of single aspect south facing apartments (which are subject to overheating)? |

|||||

|

DES44: Noise, air and light pollution |

Is the proposal designed to respond to and minimise the impacts of noise, air and light pollution? |

||||

|

6.Highqualityandsustainablebuildingdesign |

Checklist |

||||

|

PRINCIPLE |

DESCRIPTION |

CHECK |

|||

|

DES45: Commercial buildings |

Do employment buildings (where appropriate) respond positively to the character and architectural traditions of the area in terms of scale, mass, form, materials and detailing? |

||||

|

Are buildings materials appropraite to the context of the sites location? If in a rural / countryside location are they of muted colours, avoiding reflective materials, to minimise visual impact? |

|||||

|

Is the ground floor of commercial buildings articulated to create a more human scale with entrances generous and welcoming? |

|||||

|

Do reception areas and office space positively contribute to the surveillance of entrance areas and forecourts? |

|||||

|

Is signage on commercial buildings in proportion with the scale of building and appropriate to the streetscape? |

|||||

|

DES46: Sustainable buildings |

Are buildings designed to minimise the use of resources and energy? |

||||

|

DES47: Living roofsandwalls |

Has the applicant agreed with the council whether living roofs are appropriate within the context of the site? |

||||

|

Is the building position and orientation suitable for the chosen living roof or wall system? |

|||||

|

Has additional structural support to the roof been allowed for as living roofs are heavier than traditional ones? |

|||||

|

DES48: Building materials |

Has the applicant considered materials with low embedded energy, materials that can be recycled and materials that have low toxicity? |

||||

|

Has the applicant considered materials from local sources wherever possible? |

|||||

|

DES49: Local energy production |

Has the applicant integrated energy efficient solutions and renewable energy production into their development? |

||||

|

DES50: Reducing water demand |

has the applicant taken steps to reduce water demand, waste and enhance efficiency? |

||||